Near the heart of Brockton Village, from the parking lot of the Pentecostal Portuguese Church at 1637 Dundas Street West, you can find a weather-worn but vibrant mural by Indigenous artist and muralist Philip Cote. This mural depicts the journey of Indigenous history in the Greater Toronto Area — from time immemorial to today.

Before there was Brockton — before roads and subdivided lots — this was a place of creeks, rivers, black oak savannah, trading posts, and trails connected to distant fishing weirs. A place lived in and cared for by the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishinaabe, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples.

For over 10,000 years, Indigenous Peoples lived along these shores, hunting and fishing along the rivers and creeks that feed Lake Ontario. The land wasn’t something to be measured, traded, or sold—it was much more than property.

The mural illustrates significant historical events through depictions of wampum belts—traditional symbols used by Indigenous peoples to record treaties and narratives. The white One Dish One Spoon wampum represents a peace agreement between the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

It also highlight key locations, such as the 5,000 year old Mnjikaning Fish Weirs near Orillia, and the Seneca village Teiaiagon.

The weirs are the likely origin of the name Toronto. These structures were used to harvest fish and the term “tkaronto,” meaning “where there are trees standing in water,” is believed to refer to these wooden poles, giving rise to the name “Toronto.”1

Teiaiagon was one of the major Haudenosaunee Confederacy’s settlement on the north-shore of Lake Ontario located only five kilometres west of what would become Brockton.

Mississaugas of the Credit

The Mississaugas of the Credit arrived in the Toronto area around 1700, after the Haudenosaunee confederacies retreated to agricultural settlements south of the Great Lakes. Unlike their predecessors, the Mississaugas did not establish permanent villages. Instead, they followed an annual cycle, moving through their traditional territories with the changing seasons.

In winter months, family groups roamed their hunting grounds—including areas that would later become Brockton—guided by knowledge of the landscape and the availability of game. Men tracked and hunted animals, while women processed the carcasses, repaired and decorated clothes, and tended to the camp.2

In the spring, families reunited at sugar bushes to tap maple trees and at French trading posts — perhaps passing through Brockton via the Carrying Place Trail to reach Fort Rouillé — to exchange the furs gathered over the winter for European goods.

The Mississaugas gathered at the Credit River for the spring salmon run, celebrating before breaking up into smaller groups again to establish summer camps. There they would plant corn, harvest berries and wild rice before gathering again in the fall for another salmon run. Cornfields along the Humber, south of Teiaiagon, were still tended by the Mississaugas of the Credit as late as 1796.3

The relationship with the land wasn’t shaped by ownership but by the environment, wildlife, and social relations.

Arrival of the British and Treaty Making

This way of life came under pressure after the American Revolution. British Loyalists and their Indigenous allies fled north into British North America, placing new demands on the land and its resources. The Mississaugas of the Credit, aware of these demands, saw better relations with the British as an opportunity to improve their community’s well-being. They initially welcomed farmers as a source of food security (if they shared), and the British as a source of gifts.4

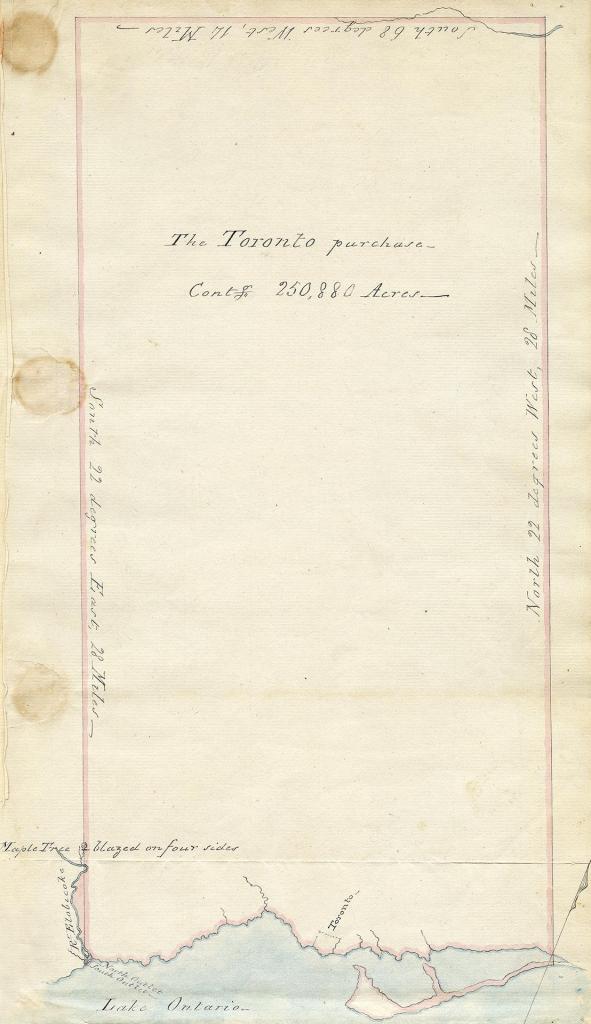

In the 1780s, the Mississaugas of the Credit and the British negotiated five land transactions, including the Toronto Purchase in 1787. The Mississaugas of the Credit negotiated each treaty and received approximately £1,000 to £2,000 in goods. However, they expected the British to continue providing gifts for the land, preserve their access to fishing and hunting grounds, and enhance their food security. This was not the case.5

Dispossession and the 1805 Toronto Purchase

By 1805, British officials sought to clarify the ambiguous 1787 agreement. That year’s treaty—signed at the Credit River—ceded over 250,000 acres, including what became Brockton. The Mississaugas of the Credit received 10 shillings. They retained fishing rights at Etobicoke Creek but were otherwise excluded from the land. However, this treaty changed key terms of the 1787 agreement.

Between 1783 and 1798, their numbers fell roughly one-thirds due to epidemics and food insecurity. European-introduced diseases like smallpox and tuberculosis swept through their communities, while the arrival of Loyalist settlers disrupted fisheries, game lands, and planting areas. Farmlands, fences, and livestock overran traditional gathering places, making it harder to survive.

In 1805, Chief Kineubenae (Golden Eagle), a Mississauga leader, expressed deep frustration:

“We were told our Father the King wanted some Land for his people it was some time before we sold it, but when found it was wanted by the King to settle his people on it, whom we were told would be of great use to us, we granted it accordingly. Father – we have not found this so, as the inhabitants drive us away instead of helping us, and we want to know why we are served in that manner… Colonel Butler told us the Farmers would help us, but instead of doing so when we encamp on the shore they drive us off, shoot our Dogs and never give us any assistance as was promised to our old Chiefs.

— Chief Golden Eagle, 18056

This statement, recorded in the official minutes of the 1805 treaty negotiations reveals the extent of betrayal felt by the Mississaugas of the Credit. They believed they were entering a relationship of alliance and mutual care. What followed was exclusion and erasure.

New systems of land ownership, settlement, and speculation replaced the traditional stewardship of the land, setting the stage for the development of neighbourhoods like Brockton on the northern shores of Lake Ontario.

The 8th Fire Prophecy

The Dundas West Mural is part of the 8th Fire Art initiative, reflecting a prophecy shared among many Anishinaabe peoples. The prophecies where given to the Anishinaabe at different stopping places along their ancient migration west from the Atlantic Coast to the shores of Lake Superior.

Earlier prophecies spoke of arrival, struggle, and broken promises. The seventh fire prophecy described a time of grief, when teachings would be forgotten and balance lost. The 8th Fire speaks of a future where Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples choose to walk together in peace and respect.7

The artist Philip Cote says,

“This 8th Fire initiative is part of an effort to ensure that Indigenous people are written back into history during the era of the 8th Fire, this time of the merging of the settlers and indigenous people. It’s time to make peace, to find common ground to talk truthfully about the land, rather than using the negative settler narratives that have dominated for so long.

– Philip Cote, Dundas West Open Air Museum

For over 200 years, there have been few reminders of the Indigenous Peoples who shaped this land for thousands of years. Since November 2024, the 8th Fire mural has stood as a vibrant expression of Indigenous presence in Brockton. Over the winter, it sustained visible damage—sections have peeled, torn, or faded. Like much street art, it was never meant to last forever. But even in its weathered state, this work of public art, which will hopefully be restored—tucked away in a small parking lot—continues to take a powerful step toward writing Indigenous people back into the story of this land.

Footnotes and Sources

- Mike Filey, “Toronto,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, last modified March 4, 2015, ↩︎

- Donald B. Smith, Sacred feathers : the Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) & the Mississauga Indians. Toronto:University of Toronto Press, 1987 ↩︎

- Johnson, Jon. The Indigenous Environmental History of Toronto, “The Meeting Place”. In L. A. Sandberg, S. Bocking, & K. Cruikshank (Eds.), Urban Explorations: Environmental Histories of the Toronto Region (pp. 59– 71). Ontario: Wilson Institute for Canadian History, 2013 ↩︎

- Smith, 1987, page 2 ↩︎

- A Treaty Guide for Torontonians ↩︎

- Smith, 1987, page 27 ↩︎

- Johnson, Jon James. “Pathways to the Eighth Fire: Mapping Indigenous Knowledge in Toronto (PDF).” 2015, pages 8-10 ↩︎

Leave a comment