Introduction

In the summer of 1791, Augustus Jones and a small team surveyed the north shore of Lake Ontario, establishing a baseline that would shape the future townships, including Toronto.

For the lands along the north shore of Lake Ontario, the transition from Indigenous land to colonial land was swift and decisive. Across a territory where Indigenous people had for millennia carved paths that followed the landscapes and seasonal movements, a new, unnaturally straight path was carved through the forests and swamps over a single summer.

This path, led by surveyor Augustus Jones and a team of European and Indigenous chain bearers and axemen, became foundational in shaping the new colonial landscape, giving Brockton Village and the entire north shore of Lake Ontario its basic modern form and setting the stage for Brockton’s emergence in the 19th century.

The Surveyor as “Lord of the Soil”

The property survey was one of the main tools of conquest. While there was a long history of surveying in the old world, it was generally used to settle property disputes and clarify who owned what. In the New World the survey was used to create new properties.1 In Upper Canada, that property was advertised in the hopes of luring British Loyalist north, on one condition: “The settlers would be merely required to subscribe to a declaration that they would defend the authority of the king in Parliament.”2

The technology required to perform detailed surveys emerged in the 17th century. In 1688, John Love published Geodaesia: or, The Art of Surveying and Measuring of Land Made Easie, a manual that became a standard guide. George Washington used it as he embarked on his first career as a surveyor.3

Surveying was critical to any colonial enterprise. Any effort to turn Indigenous land into British property required a surveyor. Soon after John Simcoe learned he would be appointed to lead a new British Province, Upper Canada, he made it a priority to find himself a Surveyor General. In June 1791, as Simcoe prepared to leave for the colony, Simcoe wrote: “I conceive that there cannot be an Office of Greater Importance to the Interests of His Majesty as Lord of the Soil.”4

The 1791 Baseline Survey

Source: Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Office of the Surveyor General, Plan Ref: SR5803 O6-4

Despite Simcoe’s pleading for a Surveyor General who would report directly to him, British authorities were already advancing the division of the lands. Three days after Simcoe wrote his letter, Augustus Jones, the New York City trained Deputy Surveyor of Nassau District (which covered what is now central Ontario), was near the mouth of Grand River when he received new instructions from Quebec to head to Humber Bay. In his notebook, Jones recorded:

“Received Instructions from the Land Board, to proceed to the Settlement Bounds of the District, and mark & Survey the front Lines of a Row of Townships agreeable to Instructions from the Surveyor General’s office.”5

Beginning on July 7, 1791, Augustus Jones with a team of 10 axe and chainmen would, with remarkable efficiency, lay down the paths of empire along the north shore of Lake Ontario, establishing what would become the major boundaries of Brockton Village: Dufferin Street to the west, Bloor Street to the north and Queen Street to the south.

Following the Shoreline

Jones began his shoreline survey on July 7, 1791, in what is now Parkdale, travelling about 450 chains (about 8 kilometres) that day along the shore until he reached a river known as Waasayishkodenayosh, later renamed the Don River by Simcoe.6

His first task was to survey the shoreline from the Humber River to the Bay of Quinte. His second was to lay out the baseline for eleven new townships. These baselines would serve as the backbone of colonial settlement.

The team consisted of ten men, at least two of whom were Indigenous. Billy, described as a “Delaware Indian,” and Wahbanosay, a Mississauga leader and Jones’s future father-in-law. Wahbanosay participated in several negotiations with the British between 1783 and 1806, including the 1805 Toronto Purchase. He bridged two eras, having followed the paths of his ancestors, he now helped lay the paths of empire.7

The team progressed quickly. On July 9, they passed the Scarborough Bluffs; on July 11, passed an Indigenous settlement in Pickering; on July 14, Farewell Creek in what is today’s Port Hope; on July 18, Smith’s Creek; and finally, on July 25, they reached the Bay of Quinte.

The journey east was relatively straightforward, hugging the shore, crossing marshes and creeks. The return journey west required a methodical and systemic approach to laying out the new grid, imposing an artificial order and logic of empire on the landscape.

A Grid for Settlement

Jones’s task was to lay out “single front townships.” This meant dividing each township using a fixed system. While not yet fully standardized, the goal was to create parcels that could be efficiently farmed, generally 100 to 200 acres.

Lots were measured at 20.00 by 100 chains (roughly 402 by 2,012 metres), with allowances for a road in front of each concession and between every fifth lot.

There were other ways this could have been laid out, 19 by 105 feet, or roads just 40 feet wide instead of 66, or a road every second lot. But, the method Jones used had specific effects on Brockton Village.8

First, the survey established the alignment of what would become Dufferin Street. While the street itself did not open until the 1850s (from Bloor southward), the 1791 plan required a 66-foot-wide road allowance every fifth lot. Dufferin sits between townships 30th and 31st lots and as a result, was reserved as a future north–south road. This lot line later became a key urban boundary, and in 1834, it was designated as the western limit of the newly incorporated City of Toronto, and in 1881 Brockton’s eastern boundary.

Second, Queen Street and Bloor Streets were laid out as the concession roads before Yonge Street was surveyed. While it would take time before these roads were carved through the forests, marshes, and oak savannas, their location was fixed by Jones, Wahbanosay, and Billy in 1791.

The Final Lines

On September 12, John Graves Simcoe was formally appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada.9 The next day, Jones was busy finishing the ground work that would lead him to his new capital on the shores of Lake Ontario.

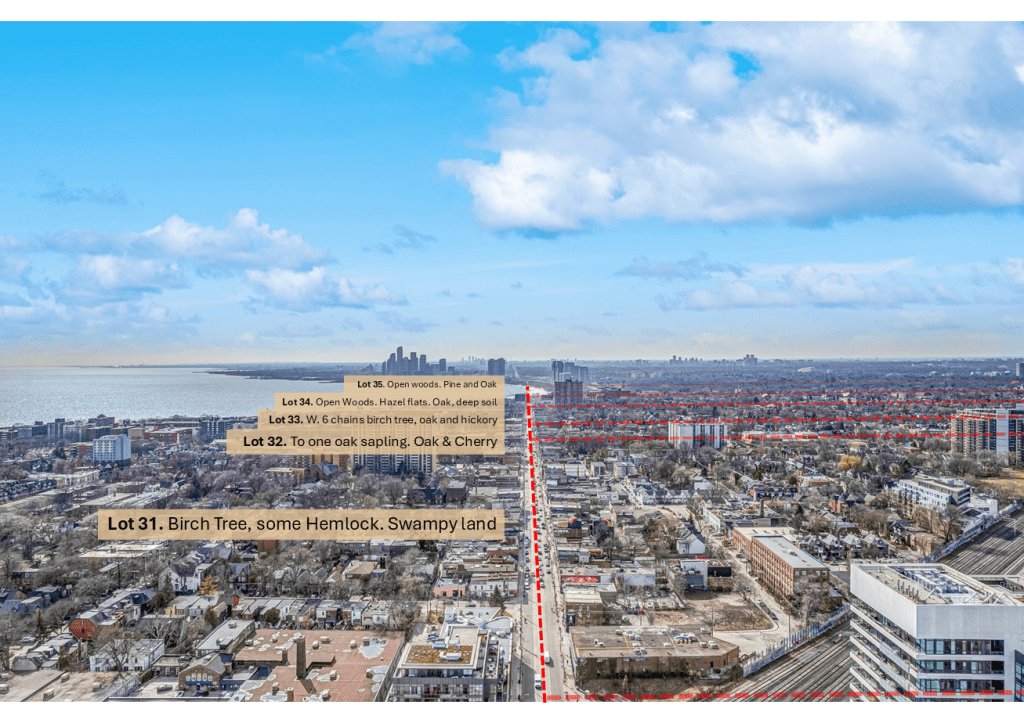

His team walked one final stretch: 4.1 kilometres along what would become Queen Street, from around Portland Street to Parkside Drive. He recorded vegetation and terrain along the way, reproduced in the map above. A lost “high point” where he encountered the Garrison Creek Ravine, swampy lands in West Queen West, the ancient oak savannah in Parkdale. It was the final line in a summer of transformation.

Two days later, on September 15, Simcoe set sail for Upper Canada to build the governmental structure that would give political and legal force to the lines Jones had drawn.

And while the city’s western boundary would eventually push out to the Humber, the logics of property and planning laid down in 1791 would structure development in Brockton to this day.

Sources

- Allan Greer, Property and Dispossession: Natives, Empires and Land in Early Modern North America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp 314. ↩︎

- Marvin L. Simner, “A Misguided Attempt to Populate Upper Canada with Loyalists After the American Revolution,” History Publications, Western University, 2023. ↩︎

- Patrick Chura, Thoreau the Land Surveyor (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2013) pp. 2-4 ↩︎

- Christopher Alexander, “David William Smith: Surveyor as State-Builder,” Ontario History 112, no. 1 (Spring 2020): 26–56 ↩︎

- Augustus Jones, Field Book No. 1, Survey Notes & Diary, 1791–2, Survey Records (L & F), Original Notebook No. 828, January 1791–September 17, 1791 / September 7, 1792–October 25, 1792 (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources), Copyright 2011, Queen’s Printer, Ontario. ↩︎

- Bonnell, Jennifer, Reclaiming the Don: An Environmental History of Toronto’s Don River Valley (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014) ↩︎

- Robert E. McGill, “Surveys and Surveyors along the Scugog,” Ontario Professional Surveyor, Summer 2013. ↩︎

- W. F. Weaver, Crown Surveys in Ontario (Toronto: Department of Lands and Forests, 1962; rev. 1968) ↩︎

- Mary L. Gray, John Graves Simcoe, 1752–1806: A Biography (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1998) ↩︎

Leave a comment