Today, the memory of the War of 1812 in Toronto us usually reduced to a few prominent landmarks like Fort York. But the war left a deeper mark on the city’s geography. The threat of American invasion didn’t just burn buildings; it forced the Crown to carve new paths through the forest. This is the story of how a crisis in 1813 finally cut the path for Dundas Street.

Last month I traced the early route of Dundas Street from the Humber up to the Davenport Trail. This post picks up the story in 1813, when the war forced the Crown to act and change the course of Dundas.

Nineteenth-century writers loved the tale of George Denison, who would become a major landowner in the west-end, opening Dundas Street during the war of 1812. Henry Scadding repeated it in 1873.1 Samuel Thompson did the same in 1884.2 It’s a good story: a local hero leading sixty men to ‘open’ the road. But the archival record tells a different, more complicated story

Here I follow the paper trail, letters, orders, and survey reports, to give a clearer account of what happened in the fall of 1813.

The Occupations of York

The backdrop is the fight for control of Lake Ontario and the occupation of York. Neither the British or the Americans held Lake Ontario in 1813. Moving supplies by boat, the easiest route, or along the shore trails was dangerous.

This weakness was exposed when American forces took York in April 1813. They stayed about a week (April 27 to May 8), then withdrew, but the threat did not disappear. On July 31st, another sizeable American force landed in town, taking what they could.3

William Dummer Powell and the Great Western Road

Following the occupation of its capital, Upper Canada’s government was in disarray. The colony’s administrator, Isaac Brock had been killed in 1812, and was replaced by Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe, who fled to Kingston after York was occupied. Disgraced he was replaced in June 1813 by Francis Rottenburg.

In York, one of the most senior government officials who remained was William Dummer Powell, a Judge and member of the Executive Committee. In the aftermath of the occupation he was scrambling to figure out how to hold on to the capital, which included trying to work out how to feed and house up to 2,000 troops he hoped the government would send to protect a town that only had about 1,500 people.4

Powell had another long-standing concern, completing the grand vision for Dundas Street. What he called “the great road through the Province.” In an August 1813 letter he wrote that he hoped to be

“instrumental in perfecting this plan [for the great road through the Province], which has for years occupied my attention, and from which I anticipated great future advantage to the Colony.”5

The crisis of 1813 gave him both an excuse and the authority to push that plan forward.

Powell’s road scheme comes apart (July–August 1813)

The very day the Americans were undertaking their second landing of York, July 31, 1813, Powell was still working somewhere in town, writing urgently to the President about roads. In a letter he warns that:

“The critical situation of the province, and the appearance of the American fleet, seem to justify any measure which can be devised immediately to restore the roads passable — the Light Brigade being obliged to operate under heavy pieces of baggage.”6

By this time, Powell had also received the July 6 general order authorizing the use of sedentary militia for road work. He reports that he has instructed Captain Thomas Hamilton of the York Militia, requesting sixty men from the 3rd York Regiment to “repair the west road of York,” and sent similar orders east to Major Rogers and Colonel Cartwright for other stretches of the “great road through the Province.” 7

But he also notes doubts had arisen “as to the practicability of Dundas Street from the Humber to Ancaster,” and decides he must inspect the route himself before giving full instructions.

This exchange suggests that the short route between the Humber and the town of York was already established and deemed practical by local military and civilians, even without a formal survey. Likely, there was already a rough and narrow path used by the military to get to Cooper’s Mill, itself following an older Indigenous trail. This is supported by anecdotal accounts of Indigenous artifacts being found near the present-day Dundas and Shaw streets intersection, suggesting the pre-existence of a route that pre-dates the 1813 road.

While Powell waits for reports from Hamilton and his superiors in Kingston, the farming season is in full swing and the harvest takes priority. Colonel Cartwright relayed the view from Kingston that the militia should not be pulled from the fields.

Three weeks later, in August 1813, Powell sounds almost defeated. He confesses that when he took on “the intended improvement of the great road through the Province,” he imagined carrying out a long-planned, coherent project. Instead, he has “miscalculated the means” of doing this without stronger backing from the administration (i.e. men, money and supplies).8

The harvest season was approaching in September. He was quickly losing window when men would finally be free to work. He also had no tools or provisions to feed the teams. With “infinite reluctance” he resigns his hope of “perfecting this plan,” and reduces the whole scheme to its “immediate benefit… in a military point of view.”

The short burst of correspondence on 24 August 1813 fills in the day to day problems.

In one note, Hamilton reports that no one along the lake will contract to feed the road parties. He can get cattle, flour, and vegetables, but only if he pays cash up front. He proposes to buy provisions on his own credit and “run myself in debt,” hoping to be repaid later. He also presses for a formal requisition for sixty men from the 3rd Regiment, warning that any delay will stall the work.9

Powell’s reply is sharp. He is furious that Hamilton has delayed his report, paralyzing the project. In a terse letter, Powell tells Hamilton he has ‘no authority to enlarge the terms.’ There will be no extra money, no new survey, and no tools. They have to make do.”10

Taken together, these letters show why the 1813 work on Dundas around York shrank to a single week in late September. The project was not blocked by ideas or surveys alone, but by timing, harvest, labour, food, money, and the limits of Powell’s authority in a capital suffering after a military occupations.

Cutting Dundas Road (September – October 1813)

Finally, nearly 80 days after the general order was issued, work on Dundas Road west of York began on 25 September ,1813. Captain George Denison took command of the local company, overseen by Hamilton. 11

The goal was critical. Secure a route between Cooper’s Mill on the lower Humber to the Garrison at the foot of Bathurst Street. This mill was one of the few sources of flour within easy reach of the capital. With American ships prowling the lake, moving flour or timber along the shoreline trails was a death sentence. Given the expected increase in troops and the impact of raids on reducing supplies, a cleared inland line, even a narrow, muddy one, would allow the garrison to move supplies without risking the boats.

On paper, sixty men were assigned to the project. It sounded like a strong force. However, the muster rolls tell a completely different story.

The “Ghost” Militia

When you look closely at the attendance for Captain Thomas Hamilton’s company between September 25 and October 3, the workforce evaporates. Over 40% of the men listed were absent without leave.

Of the sixty men assigned to cut the road, nearly two dozen simply didn’t show up. This wasn’t necessarily an act of cowardice, but of survival. It was harvest season. These militia men were farmers first and soldiers second; if they didn’t bring in their crops in late September, their families would starve in the winter.

This was not a months-long project. It was a frantic, week-long push to hack a path to the mill. Because of the labor shortage, only the portion of the road in York Township was actually laid out and improved. The Etobicoke section, which Powell had personally inspected and hoped to complete, was abandoned for the season.

The militia achieved the bare minimum, they tore out enough stumps to turn a footpath into a serviceable cart road to the Humber, and then they went home to their farms.

“Dundas Street has never been laid out through this Township” (Etobicoke, 1814)

The crisis of 1813 had forced a week-long scramble that opened a path to the Humber. But the moment the militia went home, the “Great Western Road” became a short, half-finished track that stopped abruptly at Cooper’s Mill on the Humber River.

In May 1814, the government finally found its footing, tripling the funding for roads, to finish what the militia had failed to achieve.12 But the newly appointed Road Commissioner in Etobicoke hit an immediate, frustrating snag.

He had money and the men, but couldn’t move. He had no official path to follow:

“as the Dundas Street has never been laid out through this Township. Consequently I cannot know where to imploy people to open a road.”13

The 1813 militia had cut a desperate path used by the Commissioner, but they hadn’t surveyed a legal, official line into the next township. The map had a hole.

The Surveyor General’s Office acted fast. On June 6, 1814, Surveyor General Thomas Ridout appointed Samuel P. Wilmot to complete the necessary survey and connect the short 1813 road to the planned western segments.14

Three weeks later, Ridout reported the new line was fixed. The logic was purely practical and military. They didn’t just pick the quickest path; they picked the safest and most reliable one:

“A line for a Road has been surveyed from Coopers Mill on the Humber to connect with Dundas Street on the River Etobicoke… avoiding the low wet lands… and extending for the most part of the way upon a ridge… the most eligible for a Road.” 15

They fixed the road to the driest, highest ground possible. The fear of American attack and the need for reliable supply lines ultimately dictated the exact location of the road, creating the permanent route that runs through what became Brockton today.

A Legacy of the War of 1812

The “opening” of Dundas Street in 1813 is not best understood through Denison’s legend, but through the records themselves.

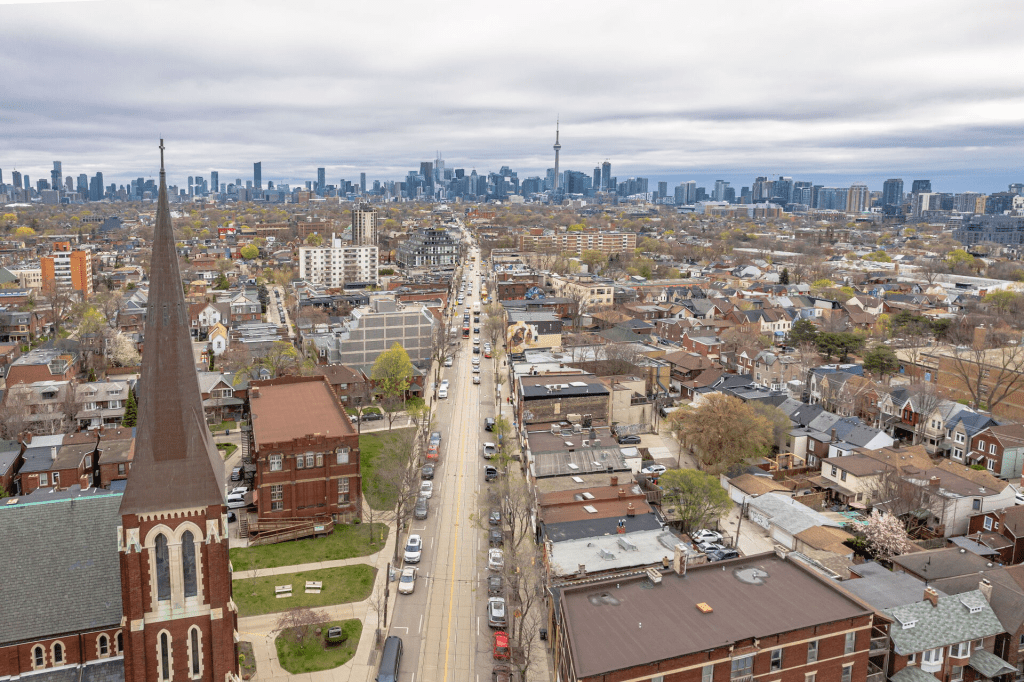

The frantic letters, the muster rolls detailing the ghost militia, and the later survey reports show the true process: a short, desperate push to keep the capital fed, followed by a formal, tactical survey. The brief American occupation forced the colonial government to draw a permanent line on the landscape. Today, when you travel Dundas through Toronto’s west end, you are driving along that quiet, silent reminder of a wartime panic that forced just one week of desperate work in the fall of 1813.

Sources

- Scadding, Toronto of Old, 371.

“As this process was necessarily slow, and after all not likely to result in a permanently good road, the proposal of Colonel, then Lieutenant, Denison, to set his militia-men to eradicate the trees bodily, was accepted — an operation with which they were all more or less familiar on their farms and in their new clearings” ↩︎ - Thompson, Reminiscences of a Canadian pioneer for the last fifty years, 118.

“In the war of 1812, Mr, Denison served as Ensign in the York Volunteers, and was frequently employed on special service. He was the officer who, with sixty men, cut out the present line of the Dundas Road, from the Garrison Common to Lambton Mills, which was necessary to enable communication between York and the Mills to be carried on without interruption from the hostile fleet on the lake.” ↩︎ - Ontario Heritage Trust, “Second Invasion of York, 1813,” Ontario Heritage Trust, accessed November 17, 2025 ↩︎

- Firth, pg 312-313 ↩︎

- William Dummer Powell, “Letter to E. McMahon Regarding the Assessment of the Great Road through the Province,” York, 23 August 1813, Upper Canada Sundries, vol. C-4543, image 493, RG 5, A-I, Library and Archives Canada ↩︎

- William Dummer Powell, “Letter … Regarding Roads, July 31, 1813,” Upper Canada Sundries, vol. C-4543, image 440, RG 5, A-I, Library and Archives Canada, ↩︎

- Powell, “Letter … Regarding Roads,” July 31, 1813. ↩︎

- Powell, Letter to E. McMahon, 23 August 1813, Upper Canada Sundries, C-4543. ↩︎

- Thomas Hamilton, “Letter to Honorable Justice Powell, August 24, 1813,” Upper Canada Sundries, vol. C-4543, image 507, RG 5, A-I, Library and Archives Canada,” ↩︎

- William Dummer Powee, “Letter to Capt. Hamilton, August 24, 1813,” Upper Canada Sundries, vol. C-4543, image 507, RG 5, A-I, Library and Archives Canada ↩︎

- Fred Blair, trans., Muster Roll and Pay List of Captain Thomas Hamilton’s Company, 3rd Regiment of York Militia, 25 September–3 October 1813, from LAC RG 9, Series 1-B-7, microfilm T-10384, vols. 17–19 (2019), https://images.ourontario.ca/Partners/TTHS/TTHS0035719951T.PDF ↩︎

- In 1812, the government approved 2,000 pounds for roads. This was temporarily increased to 6,000 pounds in 1814. See: https://bnald.lib.unb.ca/legislation/act-granting-his-majesty-certain-sum-money-out-funds-applicable-uses-province-defray-3. ↩︎

- James Smith, “Letter May the 15, 1814” Upper Canada Sundries, vol. C-4543, image 1339, RG 5, A-I, Library and Archives Canada ↩︎

- Surveyor General’s Office, “Report on the Road Through Etobicoke,” Upper Canada Sundries, vol. C-4543, image 1445, RG 5, A-I, Library and Archives Canada ↩︎

- Surveyor General’s Office, “Report on the Road from the Humber to the River Etobicoke,” York, 26 June 1814, Upper Canada Sundries, vol. C-4544, doc. 8533, image 39, RG 5, A-I, Library and Archives Canada, ↩︎

Leave a comment