Over at Spacing Magazine Cheryl Thompson wrote an excellent piece on racial discrimination at Toronto’s nightclubs, while noting that this year, Black History month feels different because of the frankly terrifying campaign in the United States to ban stories and books about “inconvenient histories.”

Brockton is often remembered as an Irish village, but what about its early Black residents? Their presence is harder to trace in official records, but glimpses appear in historical accounts—one of which reveals the racial discrimination they faced in mid-19th century Toronto.

A search of digitized newspapers led to the story of the Garnet family—one that, like Cheryl Thompson’s research into racial discrimination at Toronto nightclubs, reveals the realities of segregation in the city. But in this case, it wasn’t a nightclub—it was public transportation at the edge of the city.

Denied a Ride

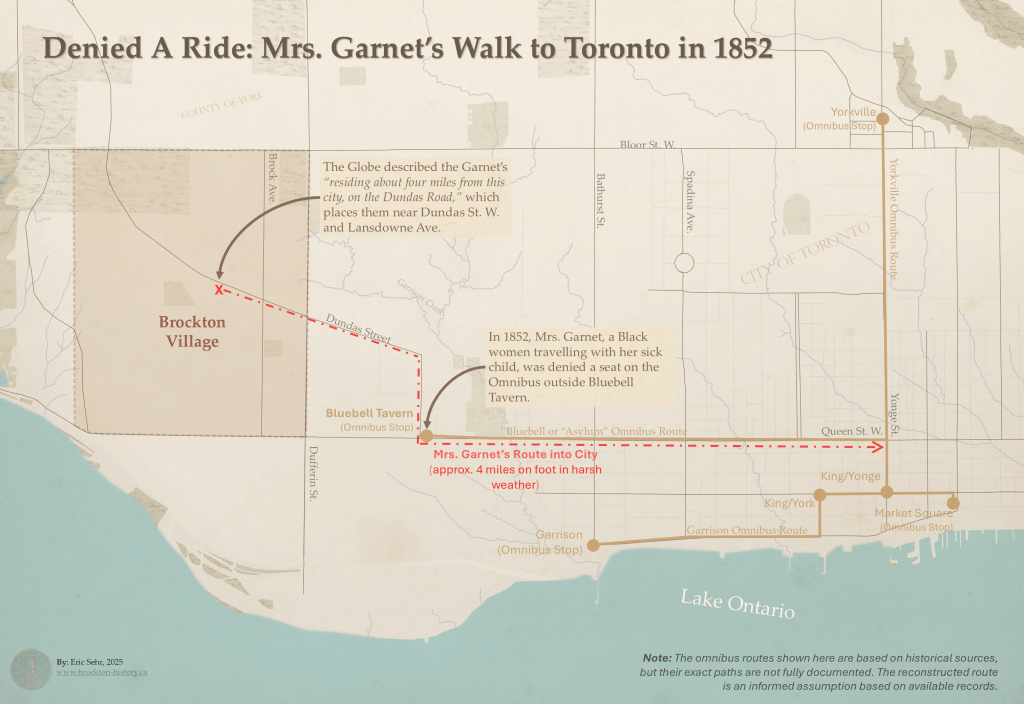

It was a raw, miserable February day in 1852. Snow fell but melted as soon as it touched the ground, turning the roads to slush. In Brockton, the Garnet’s, a Black family, needed help. Their child was ill, and they had to find a doctor in the city, 6.5 kilometers (4 miles) away.

Mr. Garnet (we don’t know their first names) left first, walking toward the city. Mrs. Garnet, carrying their sick child, planned to follow – but she would pay for a seat on the City Omnibus to spare the child the harsh journey.

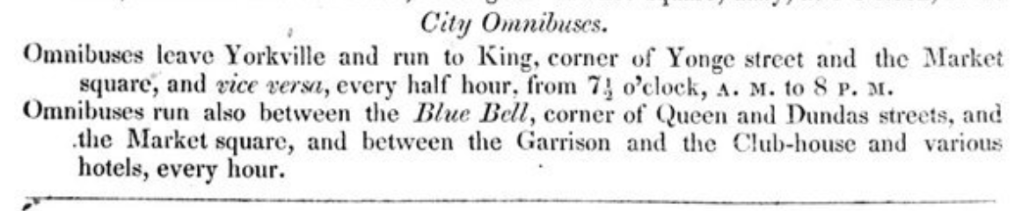

The Omnibus was the very first public transit in Toronto. They started spreading around Europe and the US in the 1830s. The first omnibus service in Toronto began less than two years before Mrs. Garnet left for the stop outside the Blue Bell Tavern with her child in her arms.

Burt Williams began the service in 1849, running his omnibuses down Yonge Street from Yorkville to St. Lawrence Market. Soon after, he started a service along Queen Street West to the market.

The emergence of regular transit service, while still a fair distance from Brockton, would have made it more appealing and accessible to live in Toronto’s rural hinterland. It was about a 20-minute walk from Brockton to Queen and Ossington (then part of Dundas Street, whose meandering route through the city has a complicated history).

When the stagecoach arrived, she stepped forward to pay her fare – but the driver, reportedly Williams son, refused. He told her that Black people were allowed to enter his bus.

Denied service because of her race, she walked into the city, her child exposed to February elements. The Globe reporting the child’s condition was critical.

A Hidden Presence

The Garnet’s story is the earliest account of Black life in Brockton Village – a history often missing from official records. In fact, it’s not even certain the Garnet family lived in Brockton. I have not been able to find them in land records, directories, or censuses.

However, the Globe places their home on Dundas Road “four miles” from the City, which would mean she was living near Lansdowne Avenue. So if we take the author at their word, the Garnets lived in Brockton.

However, given the editorial tone of the article the writer may also have exaggerated the distance. But they certainly lived in the area on Dundas Street, somewhere between Lansdowne and Ossington (see the Map).

Responding to Mrs. Garnets denial of service, the Globe wrote:

“We hope that the perpetrators of this disgraceful act as, on reflection, become ashamed of it, and will never repeat it. Let our Republican neighbours enjoy a monopoly of such acts of barbarity, but let them never be heard of in our free country.”

We don’t yet know whether Williams’ Omnibus had a pattern of racial exclusion or if this was an individual act of discrimination. However, the fact that it was reported in the press suggests that it was unusual, or because it may have cost the child their life, especially egregious. Would denying a healthy young Black man a ride have promoted a media response?

Ironically, even though Mrs. Garnet was being denied a seat on an omnibus, one of Toronto’s wealthiest Black residents, James Mink, would establish his own omnibus service along Yonge Street in 1858. Mink, a successful businessman, owned a downtown hotel and a stagecoach line to Kingston.

Williams and Mink were fierce competitors, with documented physical altercations between their drivers.1 While their rivalry was likely driven by business, there may also have been a racial dimension. Did Mink see an opportunity to serve a Black community that Williams excluded? Mink’s entry into the business suggests the possibility, though available sources may not reveal the full story.

Regardless, Minks success highlights an important contrast: while individual Black entrepreneurs could thrive in Toronto, racism still shaped who had access to public spaces—as Mrs. Garnet’s experience painfully illustrates.

What’s Next

In her Spacing Magazine article, Cheryl Thompson reflects on why we continue telling these stories, writing:

“Like so many other groups who have endured discrimination, we share these stories, especially during Black History Month, to heal. This is the restorative work that must reside at the heart of equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts, so that we never forget that Black life is much more than an acronym. It’s about the innumerable stories of life, joy, and community, many of which have yet to be told.”

Historical research is not only about documenting injustice, but uncovering the life, joy, and community that history has overlooked.

For the next post, I’ll turn to the Brockton’s earliest censuses to explore what it reveals about Black life in and around Brockton. While the census data has many limitations, it is one approach to step beyond stories of discrimination and marginalization to uncover the broad brush-stroke of life and community at a moment in time.

The Source

The Globe, February 28, 1852 – Disgraceful Conduct

Note: The term “coloured” was commonly used in historical sources but is now considered outdated and offensive.

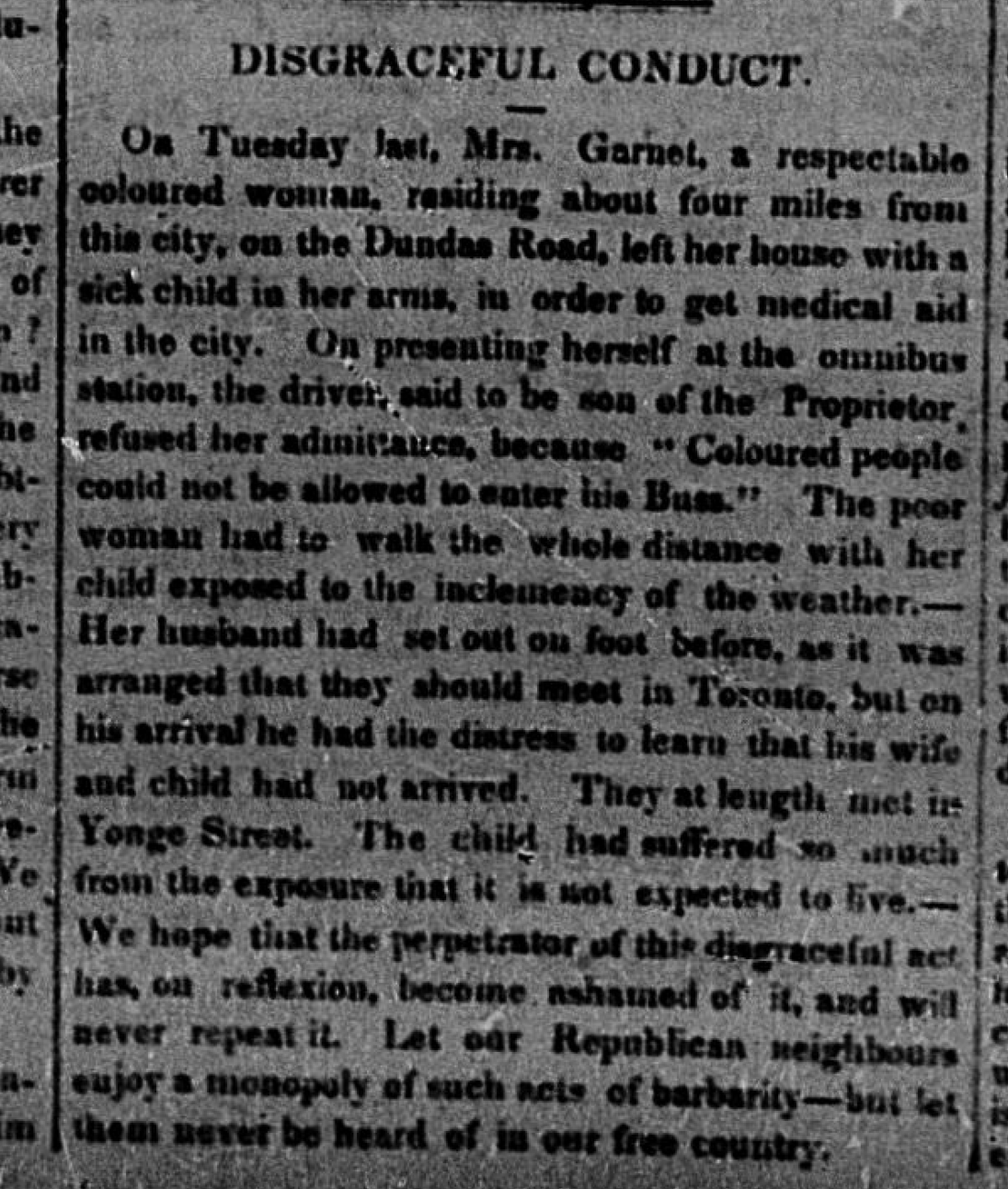

DISGRACEFUL CONDUCT

On Tuesday last, Mrs. Garnet, a respectable coloured woman, residing about four miles from this city, on the Dundas Road, left her house with a sick child in her arms, in order to get medical aid in the city. On presenting herself at the omnibus station, the driver, said to be the son of the Proprietor [Burt Williams], refused her admittance because “Coloured people could not be allowed to enter the Buss.”

The poor woman had to walk the whole distance with her child exposed to the inclemency of the weather. Her husband had set out on foot before, as it was arranged that they should meet in Toronto, but on his arrival, he had the distress to learn that his wife and child had not arrived. They at length met in Yonge Street. The child had suffered so much from the exposure that it is not expected to live.

We hope that the perpetrator of this disgraceful act has, on reflection, become ashamed of it, and will never repeat it. Let our Republican neighbours enjoy a monopoly of such acts of barbarity—but let them never be heard of in our free country.

Works Consulted

- Cheryl Thompson, “Black History Month 2025: Racial Discrimination at Toronto’s Nightclubs,” Spacing Toronto, February 12, 2025, https://spacing.ca/toronto/2025/02/12/black-history-month-2025-racial-discrimination-at-torontos-nightclubs/.

- Heritage Toronto. “James Mink and the Centuries Long Lie.” Heritage Toronto. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://www.heritagetoronto.org/explore/being-black-on-king-map-tour/james-mink-and-the-centuries-long-lie/.

- “Disgraceful Conduct.” The Globe (1844-1936), February 28, 1852. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://ezproxy.torontopubliclibrary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/disgraceful-conduct/docview/1510616632/se-2.

- “Editorial Summary.” The Globe (1844-1936), July 22, 1858. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://ezproxy.torontopubliclibrary.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/editorial-summary/docview/1513604402/se-2.

- In July 1858, a driver of Minks omnibuses was fined for “wilfully running his vehicle against a bus belonging to John Williams.” ↩︎

Leave a reply to Mapping Black Households in West Toronto, 1861: What the Census Reveals – Brockton: A Lost Toronto Village Cancel reply