In our last article, we uncovered the story of Mrs. Garnett, who was denied a ride on the omnibus in 1852. Her experience offers a rare glimpse into Black life in Brockton’s formative years. But was she an outlier? Were there other Black families living in Brockton? How did Brockton compare to other west-end Toronto communities at the time?

To answer that, I turned to one of the best sources available: the 1861 Census. While imperfect — it lacks addresses, consolidates large areas, and may have omitted up to 20 percent of Black individuals in the province — it still offers a rare window into where people lived in the spring of 1861, and how they fit into mid 19th century Toronto’s western edge.1

The Census Challenge: Locating Households in the West End

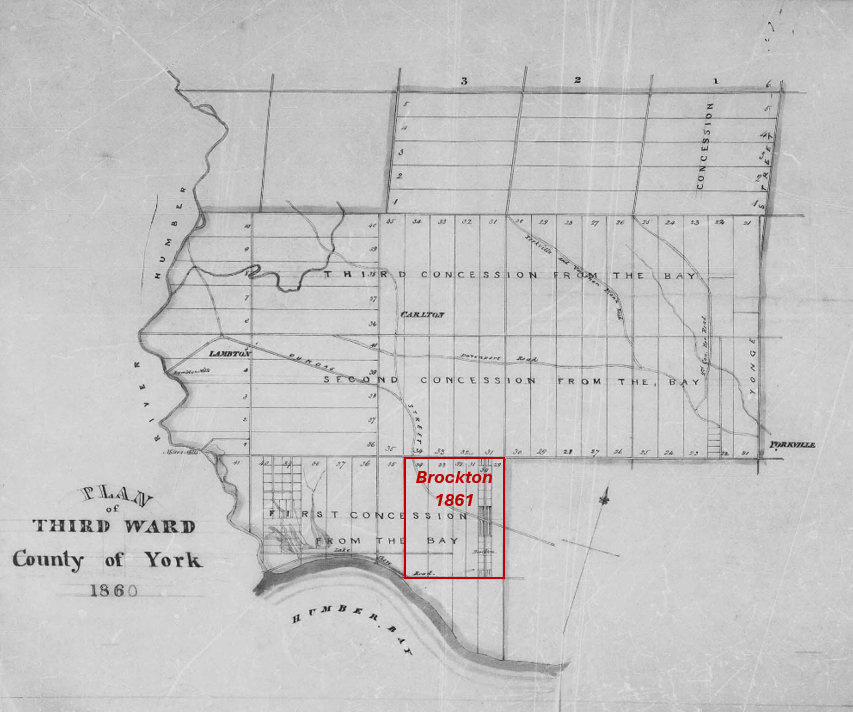

One major challenge in using the 1861 Census is that individual addresses were not recorded. Instead, data was compiled under large administrative districts. Brockton, for example, was part of the County of York’s Third Ward, which extended from the lake north to Lawrence Avenue, spanning the area between the Humber River and Yonge Street. The County of York itself had the largest Black population outside of Toronto’s St. John’s Ward.2 This vast coverage (see below) makes it difficult to pinpoint specific households within Brockton itself.

To determine place of origin of the families who lived in Brockton at the time and whether this was typical of Toronto’s west end, I focused the census search on the following areas:

1. The area south of St. Clair Avenue, which covers Brockton and its surrounding villages.

2. Toronto’s St. Patrick’s Ward, the city’s westernmost ward, which may have included the Garnet family.

By following the order in which census takers recorded names and cross-referencing them with the 1866 York Directory and 1860 Tremaine’s Map, I was able to reconstruct an approximate route.

The census taker began at Dundas and Jane Streets, moved south through Swansea, along Queen Street, then north through Brockton, up to Davenport Village, east to Seaton Village, and back west along Davenport Road to Lampton before heading east along Dundas ending at Dundas and Keele.

St. Patrick’s Ward proved to be more straightforward, as the census provided addresses.

The result? The map below is an initial attempt to visually reconstruct the Black community in Toronto’s west end on the eve of the American Civil War (click the image to expand).

Brockton and Black Settlement: What the Census Reveals

This map plots the households identified in the census across Brockton, Seaton, Carleton, Lambton, and Toronto’s St. Patrick’s Ward. Brockton stands out. While Black families lived and worked near Brockton, census records do not reflect a permanent presence in 1861.

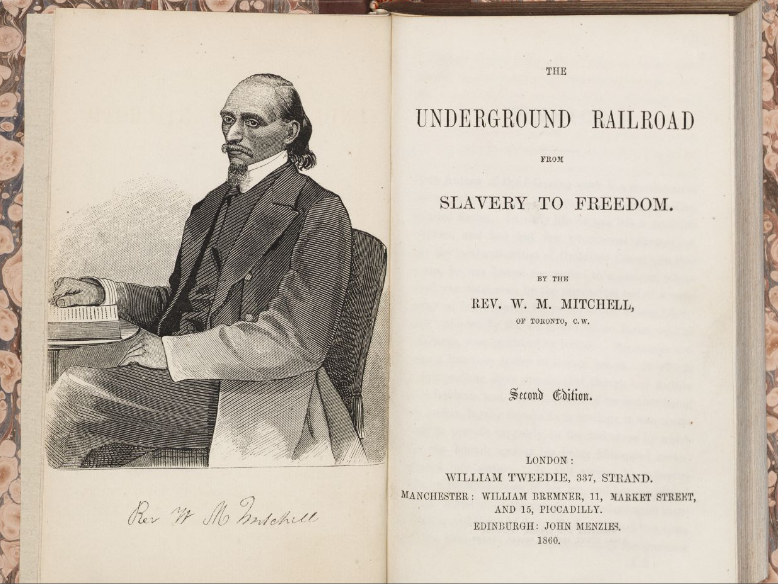

The most vibrant Black community was, of course, concentrated in Seaton Village and along Davenport Road. In The Underground Railroad: Next Stop, Toronto!, Adrienne Shadd, Afua Cooper, and Karolyn Smardz Frost document the lives of many community members, including stalwarts Deborah and Perry Brown, Underground Railroad refugees Frank and Emily Wanzer, and Barnaby and Mary Grigsby.3 They also highlight Baptist minister and abolitionist Rev. William Mitchell, entrepreneur and “iceman” Richard B. Richards, and Jefferson and Mary Pipkins, who reached Toronto, but were forced to leave behind their enslaved children.

However, the mapping reveals an interesting secondary cluster south of Seaton, along Claremont Street (then called Bishop Street), which hasn’t been much discussed in existing sources of Toronto’s Black History.

Closer to Brockton, two households were recorded south of Queen Street. These included James Harrison and Henrietta Phillips, who lived in house of Toronto’s most prolific early builders, John Ritchie.

The second household belonged to Dennis Rhodes and Sara Smith. Dennis is a formerly enslaved man from South Carolina who settled near Humber Bay. His obituary in the Toronto World decades later described him as a well-known community figure.

As a recent arrival from the United States in 1861, Dennis Rhodes story seems typical of the area. While about 45% of Black residents in this area were born in Upper Canada, they were mostly children, suggesting they were children born to African-American parents. Those born in the U.S. had an average age of 37 compared to 11 years old for those born in Canada, reinforcing that Toronto’s west end was home to many new arrivals— fleeing the United States in the 1850s.

Brockton: A Place Black Residents Passed Through, But Didn’t Settle?

York County’s rural setting and proximity to Toronto attracted many U.S. migrants in the 1850s. Black families lived and worked near Brockton, but census records show no permanent presence in 1861.

Black workers and families were likely present—but primarily as day labourers rather than property owners or renters. As Shadd, Cooper, and Smardz Frost note, many men laboured in clearing land, hauling goods, and building homes, while women worked as market gardeners or washerwomen.

There is some evidence of this on Dundas Street, just east of Brockton. George Taylor Denison recorded a diary entry on July 10, 1851, offering a first hand account of this type of day labour:

“Two Black men waited all morning for work. Hired them to mow the lawn, gave them lunch, and paid them 3 shillings and 9 pence. Tomorrow they clear the swamp meadow—two dollars for the job.”

Denison’s account suggests a transient Black workforce taking short-term jobs but not settling permanently.

What Shaped Settlement Patterns in Toronto’s West End?

Access to social, cultural, and religious institutions played a significant role in shaping settlement patterns. Churches, fraternal organizations, and benevolent societies were primarily concentrated in the city, providing essential support networks that influenced where families and recent migrants chose to live. Looking at the map, only five of the 28 households (17%) were located west of Garrison Creek—two of them tied to service jobs at an inn and a wealthy household—suggesting a preference for settling in the city’s closer suburbs rather than in more isolated areas farther west. In this regard Dennis Rhodes and Sara Smith were not the norm.

Discrimination also shaped Black settlement. Irish immigrants and Black workers competed for unskilled jobs, especially in railway construction and farm labour. With Brockton’s large Irish population, employment and housing opportunities may have been more limited.4

Black people where living and working in every part of West Toronto —contributing to its economy, shaping its surrounding neighbourhoods, and building lives in the area—even if census records do not reflect a permanent presence in every village in the spring of 1861.

While we’ve been exploring Black life in Brockton’s early years, our next articles will examine how Indigenous land was taken and shaped in the late 18th century. These foundational pieces will provide context for future research into how different communities—Black, Irish, and others—moved through and shaped the area over the 19th century.

Sources and Notes

- Wayne, Michael. The Black Population of Canada West on the Eve of the American Civil War: A Reassessment Based on the Manuscript Census of 1861.” Histoire sociale / Social History 28, no. 56 (1995): pg 469. https://hssh.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/hssh/article/view/16644. ↩︎

- Shadd, Adrienne, Cooper, Afua, and Karolyn Smardz Frost. The Underground Railroad: Next Stop, Toronto!. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2022 ↩︎

- Note: Shadd, Cooper, and Frost write that Wanzer and Grigsbys shared a frame house next door to Deborah and Perry Brown in Seaton Village. However, their location in 1861 is unclear. Their placement in the 1861 census suggests they may have been as far west as Davenport. However, I have chosen to show them in Concession 2, Lot 27, which is were the 1866 Directory places them. ↩︎

- Janet L. Silverthorne, Unwelcome Guests: Canada West’s Response to 19th-Century Black Refugees (Toronto: Umbrella Press, 2006), pg. 62. ↩︎

Leave a reply to BN004 || Some reflections after six months – Brockton: A Lost Toronto Village Cancel reply