Brockton’s First Land Owners

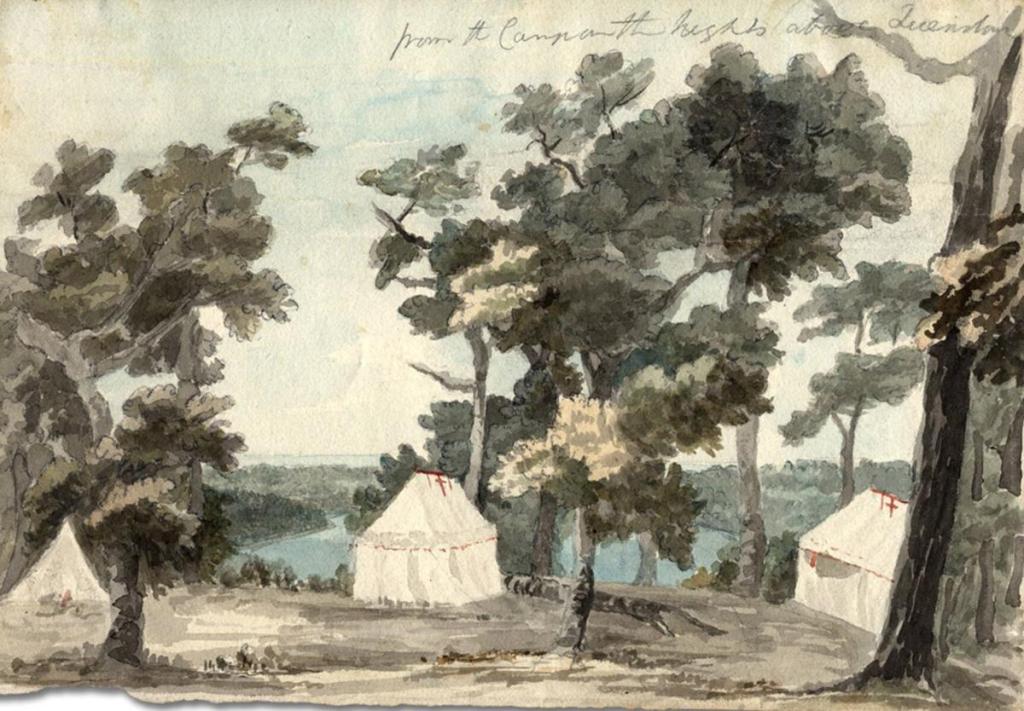

In the summer of 1793, John Graves Simcoe arrived in Toronto determined to establish his new capital on the remote northern shores of Lake Ontario. He brought soldiers, his family, a canvas tent, and an eagerness to erase the area’s Indigenous presence and make his mark the British Empire in North America.

Near the foot of today’s Bathurst Street, in a small canvas tent that doubled as both the Simcoe’s family’s home and the Provincial council chamber, Simcoe met with his Executive Committee to review the “Maps and Surveys of the Town and Township of York.”1 From those maps, and working through a stack of petitions from colonialist, Simcoe began distributing land as reward for service to the new province and compensation to encourage officials to move to the new Town of York.

The Executive Committee met for three days in early September 1793, granting 75 percent of the land between the First Concession (now Queen Street) and Second Concession (now Bloor Street).2 This paper exercise, matching petitions to parcels, meant much of the land was now owned, but it was mostly a city on paper. Most grantees, especially on the outskirts of the new town were not planning on moving to or developing their lots.

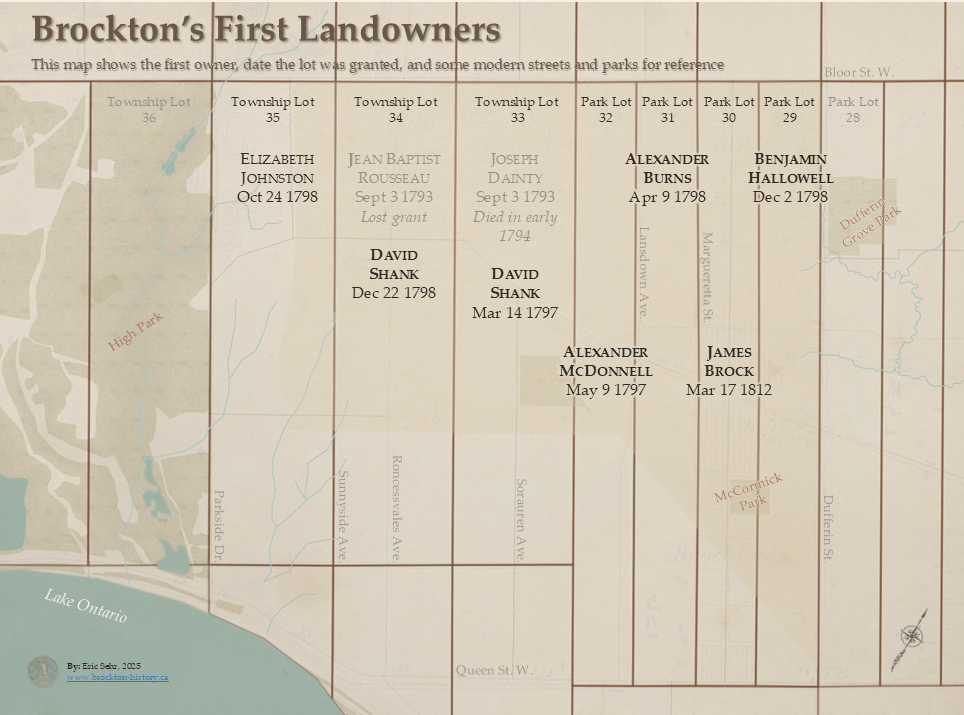

In fact, at the western edge of the map, the seven lots that would later become part of Brockton – Lots #29 through #35 – were not granted until four to five years later.

This post introduces most of first landowners of what would become Brockton. They didn’t personally farm it, build on it, or live here. But they held the land, and on paper, that was what mattered.

Brockton’s First Landowners (1797-1812)

The earliest landowners of what would become Brockton Village don’t play any direct roles in a local history. They were given the land between 1797-1812 as a payment for their or their family members service the British Empire or new province. There were two early land grants in 1793. Jean Baptiste Rousseau was granted Lot 34, but sold it to David Shank soon after. Joseph Dainty was granted Lot 33 but died soon after.

There were two types of lots in Brockton, which were surveyed between 1791 and 1793. The standard 200 acre Township Lots and the more unusual 100 acre Park Lots, which were Township Lots split in half, to provide more parcel to give away near the town.

Park Lot 29 – The Chief-Justice’s Father-in-Law

Benjamie Hallowell arrived in York in 1797, joining his son-in-law, Chief Justice John Elmsley. Elmsley, would take possession of Park Lot after Hallowell’s death in 1799.

Park Lot 31 – The President’s secretary

Alexander Burns served as secretary to Peter Russell’s, President of the Executive Committee while Simcoe was back in England. His grant of Lot 31 was likely compensation for modest pay, and like many bureaucrats, he held the land on paper but did not develop it.3

And yes—Upper Canada briefly had a “President.” While Simcoe was away, Russell acted as Administrator and President of the Executive.

Park Lot 32 – The Sheriff

Alexander McDonnell was one of the few Catholics to receive a land grant in Anglican York. A veteran of Butler’s Rangers during the American Revolution, McDonell went on to serve as Sheriff of the Home District, which covered most of South-Central Ontario, from 1792 to 1805. He later became a member of the Upper Canadian Parliament and amassed over 10,000 acres of land. In 1821, he wrote

“I have about 10,000 acres of valuable land in the best situtations but I have not been able to realize a dollar on them.” 4

– Alexander McDonnell, Nov. 3, 1821

Township Lots 33 and 33 – The Commander

David Shank was a Scottish-born Loyalist officer whose military career placed him close to the core of British colonial power in early Upper Canada. When the Queen’s Rangers were re-formed in 1792, Shank volunteering to go to Upper Canada, rising through the ranks to lieutenant-colonel by 1798. He served as acting commander of British forces in Upper Canada after Simcoe’s departure. It was during the time he served as commander of British forces that he was granted Lots 33 and 34.5

Shank had also received Park Lot 21, between what is now Manning Avenue and Gore Vale Avenue east of Trinity Bellwoods, making him one the west ends largest landholders.

Township Lot 34 – The Widow

Elizabeth Johnston wasn’t a colonial functionary but a widow. By the 1790s she was blind and looking for a payout, which she felt was owned to her, due to her husbands long service as a translator with the British Indian Department.

Why it matters

These first owners of Brockton were not settlers or community builders. They were colonial functionaries and exiled loyalists. The land was given as payment, patronage, or charity. It would be decades before these lots were sold off, subdivided, and filled with streets, houses, and lives.

One lot we didn’t look at was Park Lot 30. The heart of Brockton Village. That will be the focus of the next post.

Sources

- Firth, Edith G. 1962. The Town of York, 1793-1815: A Collection of Documents of Early Toronto. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pg. 11 ↩︎

- Smith, Wendy. “The Toronto Park Lot Project.” The Toronto Park Lot Project. Accessed December 22, 2024. https://parklotproject.com/. ↩︎

- Firth, Edith G. 1962, pg. 33 ↩︎

- Brother Alfred, Catholic Pioneers in Upper Canada (Toronto: Macmillan, 1947), 25, https://archive.org/details/catholicpioneers0000unse/page/25 ↩︎

- Archaeological Services Inc., Stage 1 Archaeological Assessment of 2238, 2252, 2264, 2280, 2288 and 2290 Dundas Street West and 104–105 Ritchie Avenue…, prepared for Choice Properties Limited Partnership (Toronto: Archaeological Services Inc., June 30, 2022), https://bloordundas.ca/docs/2280DundasStW_Archaeological%20Assessment_20220630.pdf. ↩︎

Leave a reply to 📓BN006 || Who owned the land in 1840? Using the Ontario’s Land Registry – Brockton: A Lost Toronto Village Cancel reply