In the spring of 1812, James Madison, President of the United States, was under pressure to deal with British meddling in American affairs and a rising clamour from Congress for war. In York (now Toronto) Upper Canada, Major-General Isaac Brock, President of the colony and Commander of British forces, was preparing his defenses while also attending to another responsibilities, granting Crown land.

It was during this tense spring, just months before war broke out, that the Brock family first left its mark on Toronto’s western suburbs. Nearly forty years later, that mark would grow into a village called Brockton.

The 1812 Grant

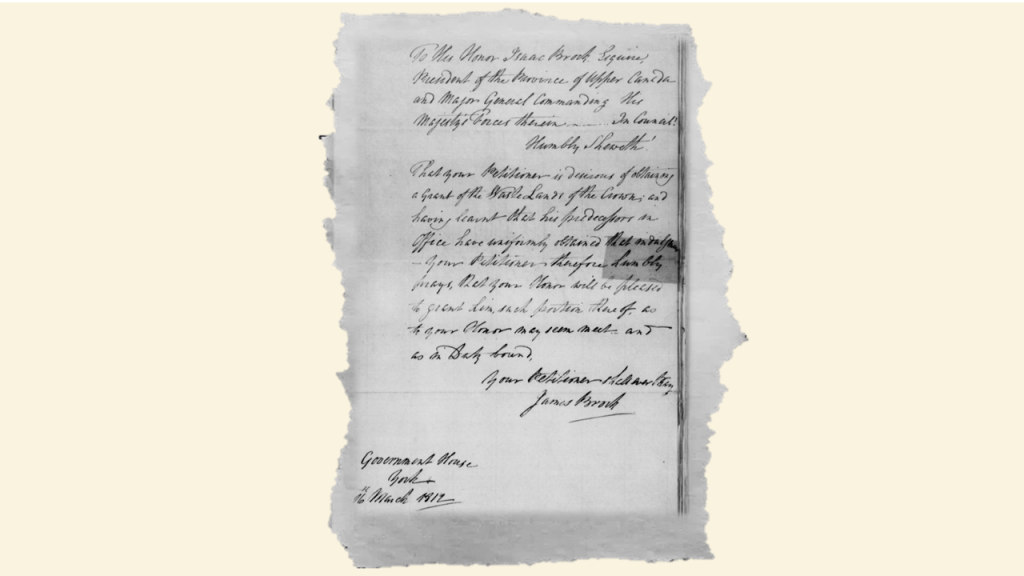

On March 16, 1812, James Brock, Isaac’s first cousin and secretary, petitioned for “a grant of the Waste Lands of the Crown…such portion thereof as to your Honor may seem meet — and as in duty bound.”1

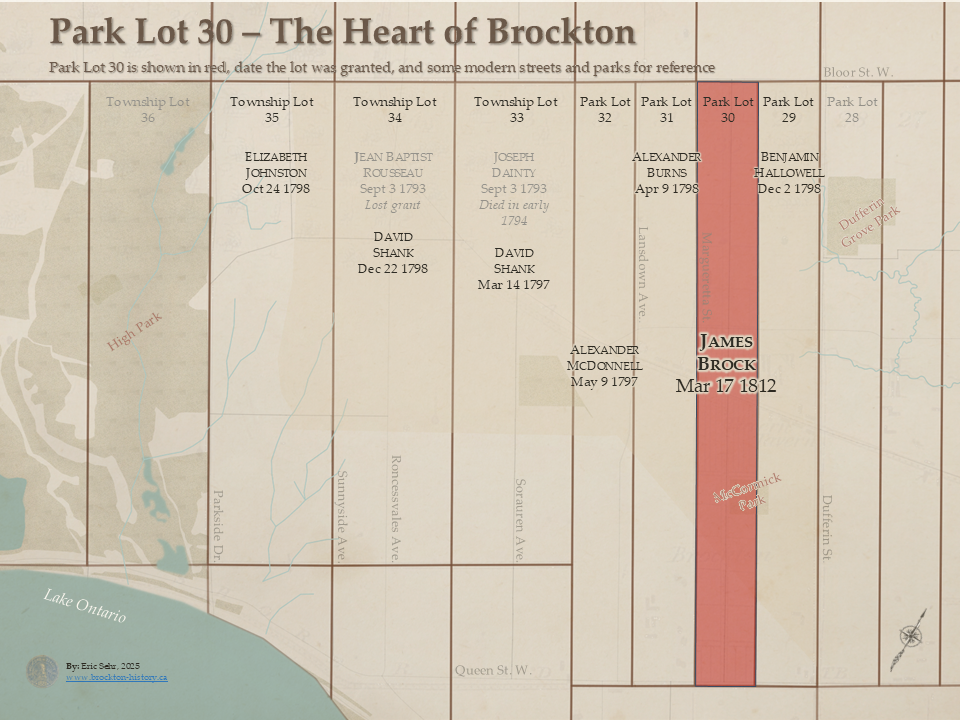

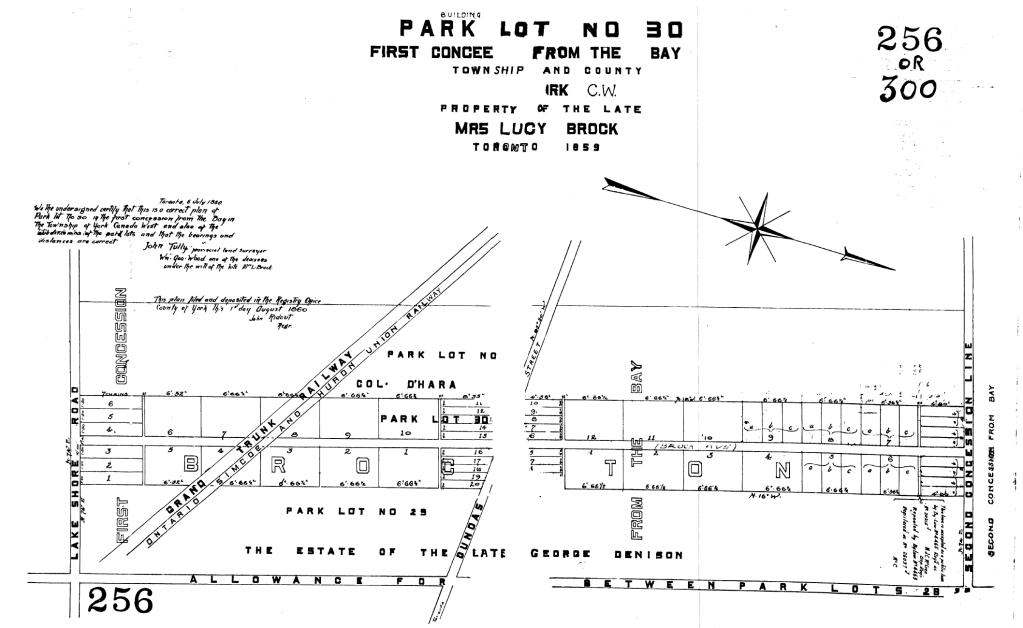

Park Lot 30 was the only park lot still unclaimed by 1812. The other thirty-one 100 acre lots had been granted in the 1790s. Why this lot remained available is unclear. Justice Henry Allcock may once have held a claim but he purchased a different parcel closer to the city in 1800, leaving Park Lot 30 untouched until James’s grant.2

The request was granted at the next Executive Council meeting. James received 1,200 acres: 400 in Marysburgh Township (now part of Prince Edward County), another 400 in Binbrooke southeast of Hamilton, and 340 acres in York Township, including Park Lot 30, a 100 acre-parcel that later formed the heart of Brockton Village.

Because of this grant, Brockton is said to be named for James Brock, rather than his cousin Isaac, who was one of the most celebrated Canadians of the 19th century. Known as the “Hero of Upper Canada,” Isaac died at the Battle of Queenston Heights leading British forces during the War of 1812. In 2009, the Friends of Fort York published an essay that argued that “Brockton’s Name Recalls Isaac Brock’s Cousin James.”

Yet, Brockton recalls all three Brocks:

Isaac, who died a hero in 1812 and whose face later appeared on Brockton’s municipal seal.

James ,who was granted the land that same spring.

And Susannah Lucy Quirke Short (known as Lucy), who inherited the land after Jame’s death and ultimately developed it into Brockton Village.

Land, Marriage, and Duty

Lucy Brock was more closely to Brockton than James ever was. The daughter of Anglican preacher Robert Short, she arrived in Canada at the age of seven and grew up in Trois-Rivières, a small community of about 800 people, mostly Catholic French Canadian. The Anglican congregation numbered fewer than twenty adults.3

Trois-Rivières also hosted a significant British garrison. More than twenty British regiments passed through in the years before the War of 1812, which is likely where Lucy and James met.4

They married in July 1812, four months after James received his land grant. By marrying James, Lucy married into the 49th Regiment of Foot. Less than a year later she was caught in the upheaval of war. Her famous cousin-in-law, Isaac Brock had been killed at Queenston Heights, York (now Toronto) was occupied by American forces, and Lucy herself was briefly captured at Fort George. She was released soon after under a flag of truce and taken to Kingston.5

Lucy rejoined James in October 1813 and would remain with him for the next seventeen years as the regiment moved across the empire. After leaving Canada in 1815, they spent time in England and Ireland before transferring to Cape Town in 1823, where a severe cholera outbreak killed about 10 percent of the unit. By 1829, the regiment was sent to India, and James died of cholera soon after arriving in Berhampur in 1830.6

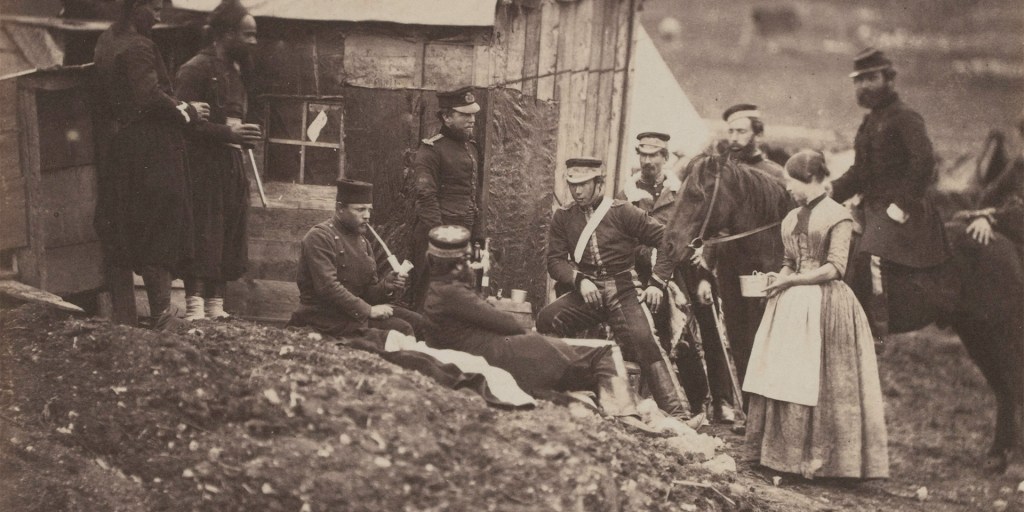

Life in the Regiment

For seventeen years, Lucy lived on the front lines of Britain’s imperial army. Women like her were almost invisible in official records, yet they were essential to regimental life. The army, with regulations for nearly everything, was silent on soldier’s wives.

Lucy likely lived a more comfortable life than most army wives. In 1803, Isaac Brock had appointed James Regimental Paymaster of the 49th (Hertfordshire) Regiment of Foot, a position he held for twenty-seven years.It was a plum appointment, under the 1797 regulations, a Paymaster earned 15 shillings a day, the same as a Lieutenant-Colonel, and second only to the Colonel.7

James’s duties were central to the regiment’s functioning: arranging the delivery of funds, paying soldiers’ wages, and maintaining meticulous financial records for the Treasury, and perhaps a chance to make some money on the side by making loans to soldiers and officers.8

As the paymaster’s wife and Isaac Brocks’ cousin-in-law, she had both visibility and authority. She likely maintained traditional domestic role, transplanted into a regimental setting, managing cooks, maids, housekeepers, and handymen, if not doing these duties herself, while also acting as a social bridge between officers’ families and the broader community. Many women in this imperial context, far from the settled life of Britain, also became their husbands’ key confidants and assistants. So perhaps she helped James, manage the books and was more active in the business of running a regiment. 9

James certainly seemed to trust her ability to manage a complex estate, granting her everything in a will, instead of a more typical dower, or leaving the estate to be managed by a male relative or trustees.

An Enterprising Widow

James’s death in 1830 was a rupture. Widowed in her early forties, Lucy had known only the rhythms of army life. Records suggest she later lived variously in London, Montreal, and Trois-Rivières. In 1837, a notice reported a “Mrs. Brock and two servants of Canada” arriving in Montreal from Liverpool.10 The 1851 Canadian census shows her living with her widowed sister in Trois-Rivières, while records from 1852–1855 place her back in London, England.

What is clear, however, is that Lucy remained devoted to her extended family, the British Army, and Isaac’s memory. Her nephew Frederick Short, writing in the 1890s, recalled:

“When I first came to Canada, Mrs. James Brock (my Aunt) was shewing me the Pictures in her Parlor and told me that [miniature] was the Portrait of Sir Isaac Brock and that he was a famous Soldier and cast up to me that if I had accepted the Commission in the British Army, which she had got the promise of for me, I might have been some day a famous man too, but as I had refused I need not expect any favours from her.”11

Park Lot 30 and the Making of Brockton

Isaac, James, and Lucy all touched Park Lot 30, but it was Lucy who most directly shaped it.

By 1850, she commissioned John Tully to survey and subdivide the property, laying out an axial road and twenty narrow lots fronting Dundas Street. Over the next nine years she sold more than three dozen parcels, preferring smallholders to a single speculator. The income supported her life in London and Montreal while establishing the settlement pattern that became Brockton Village.

Even after her death in 1859, Lucy’s name lingered locally. At an 1865 murder inquest, a witness described simply living on “Lady Brock’s land.”12

And yet, public memory shifted. In 1884, when Brockton adopted its municipal seal, it was Isaac Brock’s face that appeared at its centre, a celebration of the “Hero of Upper Canada,” even as the village itself grew along the lines Lucy had set.

Conclusion

Park Lot 30 carries all three Brocks within it: Isaac’s name, James’s grant, and Lucy’s survey. Isaac’s heroism gave the village its identity, James’s petition linked the family to the land, but it was Lucy, who lived and moved easily across the empire for forty-years, whose quiet decisions turned Park Lot 30 into the beginnings of a community.

References

- James Brock, land petition, York, 1812. Upper Canada Land Petitions, B 10, Petition 66 (LAC RG 1 L3, C-1623) ↩︎

- “The Toronto Park Lot Project,” Park Lot 30, accessed September 6, 2025, https://parklotproject.com/ ↩︎

- Arthur Ernest Edgar Legge, The Anglican Church in Three Rivers, Quebec, 1768–1956 (Russell, ON: [Publisher not identified], 1956), 54, https://archive.org/details/trent_0116301868513/page/54/mode/2up ↩︎

- Legge, Anglican Church in Three Rivers, 156. ↩︎

- Dan Brock, John England, Gillian Lenfestey, Stephen Otto, Guy St-Denis, and Stuart Sutherland, “Brockton’s Name Recalls Isaac Brock’s Cousin James,” The Fife and Drum: The Newsletter of the Friends of Fort York and Garrison Common 13, no. 1 (March 2009): 1. ↩︎

- F. Loraine Petre, The Royal Berkshire Regiment (Princess Charlotte of Wales’s), Vol. 1: 1743–1914 (Reading: The Barracks, 1925), 111–119, https://archive.org/details/berkshireregtvol1/page/111/mode/1up ↩︎

- Brock et al., “Brockton’s Name Recalls,” 1. ↩︎

- Richard Tennant, “Wellington’s Money,” The Napoleon Series, accessed September 6, 2025, https://www.napoleon-series.org/military-info/organization/Britain/Miscellaneous/Paymasters/Wellington%27sMoney.pdf ↩︎

- Verity G. McInnis, “Indirect Agents of Empire: Army Officers’ Wives in British India and the American West, 1830–1875,” Pacific Historical Review 83, no. 3 (August 2014): 381-384, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/phr.2014.83.3.378 ↩︎

- Montreal Gazette (Montreal, QC), September 12, 1837, 2, https://montrealgazette.newspapers.com/image/705302674/ ↩︎

- Guy St-Denis, The True Face of Sir Isaac Brock (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2018), 39, https://press.ucalgary.ca/books/9781773850214/ ↩︎

- The Globe (Toronto), Inquest held at McGuire’s Tavern at Queen and Dundas Street. September 12, 1865, 1 ↩︎

Leave a reply to A Road Cut in Crisis: Dundas Street and the War of 1812 – Brockton: A Lost Toronto Village Cancel reply