LAC, Acc. No. 1934-402

Dundas Street is central to the history of Brockton, but it’s also a puzzle. Its early course is tangled in contradictory sources, and it’s route through Brockton was never formally surveyed. 1

Dundas was conceived as part of a much larger imperial project. British officials imagined it as a military and settlement corridor linking the colony from east to west: from the Thames River (London) through the Head of the Lake (Hamilton) to York (Toronto) and, eventually, to Lower Canada (Quebec).

A Road Through Indigenous Land

Segments of Dundas Street were already being built in the 1790s near London and Burlington, but west of York the plan met resistance. The land was still Mississauga territory. Valuable not just strategically but as the Mississaugas’ main remaining hunting and fishing grounds.

When the Crown proposed to buy the land, the Mississaugas named a price the British refused to pay. For nearly a decade that impasse frustrated efforts to link York with the western part of the province. Unlike Yonge Street, which advanced quickly through Crown land, Dundas remained largely an ambition on paper.2

In 1805, the British again sought to negotiate a right-of-way west from York. The result, Treaty 14, the “Head of the Lake Purchase,” was ratified on September 5, 1806.3

Yet even before the treaty was finalized, the British were impatient to proceed. A notice in the Upper Canada Gazette that August announced:

“Notice is hereby given that the commissioner of highways of the Home District…to receive proposals and to treat with any person or persons who will contrive to open and make a road called Dundas street, leading through the Indian reserve on the River Credit, and also to erect a bridge over the said river at or near where the said road passes.”4

Until the 1806 cession, the Crown lacked legal authority to open or fund a road west of Etobicoke Creek to York. By 1807, Dundas Road was being opened north of the old informal trail in the Head of the Lake purchase as a major concession road.

An Unfinished Vision

Through the first decades of settlement there was little reason to formalize Dundas through what became west Toronto. Traffic was light; unlike Yonge Street, settlement wasn’t organized along it, and the trail crossed lots held by absentee landlords.

The lack of formal surveys and shifting routes also confounded local officials responsible for maintenance. One, accused of failing to spend his road budget, explained:

“The money in my hand for the purpose of repairing the Roads has not been as yet expended… there being some difference in opinions respecting the mode of establishing Roads. I strenuously oppose having the money laid out where there is every probability the road may soon be altered… I wish to ascertain where the Country Town may be established, that the Road to & from it may be benefited as much as possible by the public money.”⁷

Existing routes—Indigenous paths and the Lake Shore road—were sufficient for local travel. The Crown’s vision of a continuous highway to York remained mostly on paper, awaiting the population, security, and funds to make it real.

Only after the first decade of the nineteenth century, when movement westward intensified and the vulnerability of the lakeshore route became clear, did the need for a stronger inland road gain urgency.

For the first twenty years, the roads settlers called “Dundas” looked nothing like they do today.

Tracing the First Dundas

Several pieces of evidence suggest that the first route called Dundas Street followed a northern path along the Davenport Trail. A 1797 map, an 1802 map, an 1813 travel guide, and the Deputy Surveyor General’s own provincial maps all point to that alignment.

But on the ground, the name “Dundas” wasn’t especially useful. Locally, routes west of York were known by their landmarks: the Humber Road, the Commissioners Road, the road to Niagara, or the road to Burlington. By 1813, “Dundas Street” existed more in bureaucratic imagination than local reality.

Had the route been more clearly established before 1806, west Toronto might today have a Niagara Road instead of Dundas, just as the east had its Kingston Road.

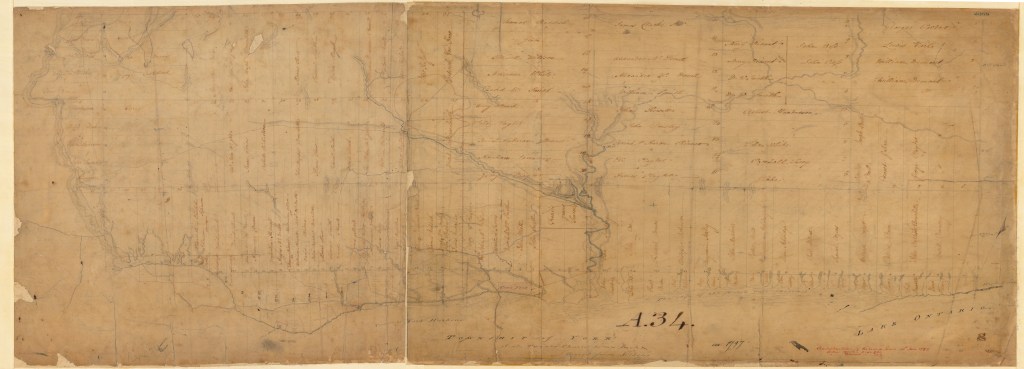

1797 Aikens Map

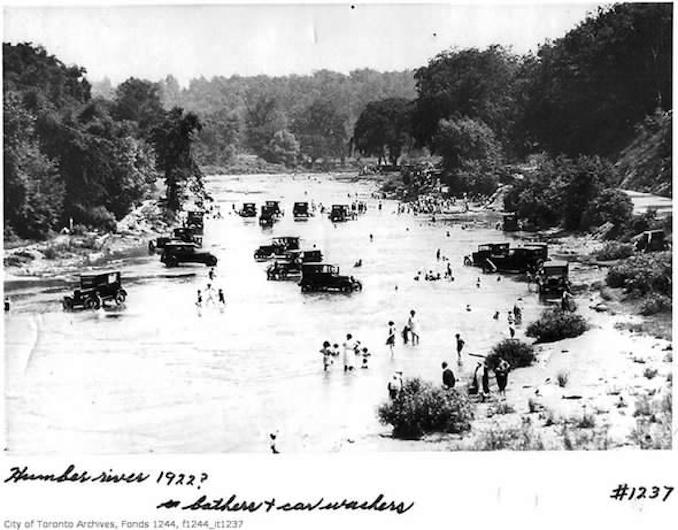

The 1797 Aitken map shows a trail stretching from the King’s Mill (the original Old Mill) north to the Davenport Trail. The same trail appears on an 1837 map of York Roads, suggesting it remained in use for at least a generation. It offered a logical overland route east from the Humber near the Seneca village of Teiaiagon—a natural site for both Indigenous and European settlement.

Here, the river could be crossed on foot in the right season. Travellers turned north along the high ground above the ravines or south toward the lake.

Even a century later, people (and cars!) still waded these same shallows below Teiaiagon.

1802 Chewett Map

This map of York between today’s Bathurst and Woodbine shows the main road west to Niagara, logically “Dundas,” the Great Western Road, following the Davenport route, not a southern alignment near the water or Queen Street.

A geographical view of the province of Upper Canada

A travel guide published in 1813 confirms that the escarpment route was known as Dundas Street:

Two miles from York, on the road which leads to Simcoe, called Yonge’s-street, another road leads out, extending to the head of the lake called Dundas-street, which is completely straight for 260 miles to the river Thames, near Detroit. Although it is not passable in all places, yet where it is not opened, there are other roads near by, which lead the same way, and enter it again.”

That description places the junction of Dundas and Yonge about two miles north of the town, precisely where Davenport Road meets Yonge today.

Chewitt’s Maps of Upper Canada

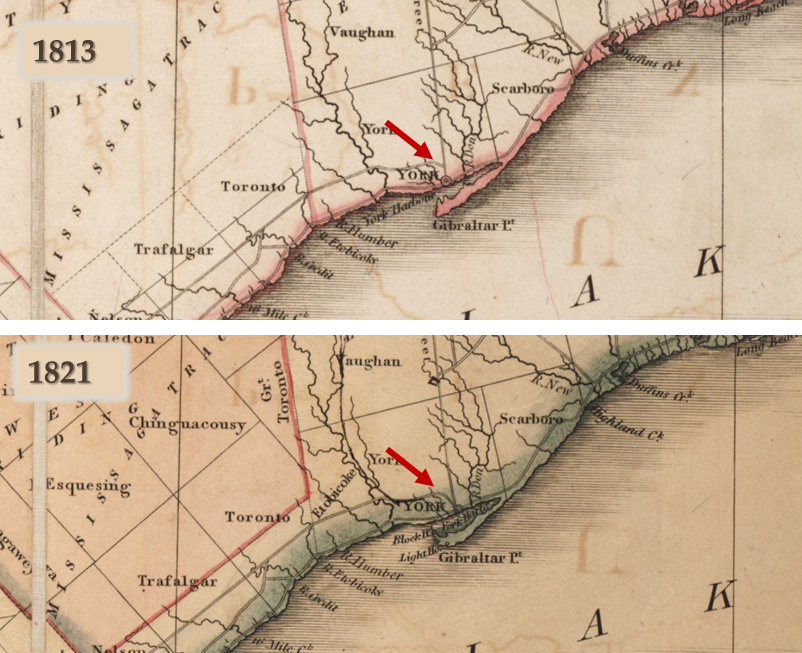

On all maps issued by the Surveyor General before 1814, Dundas joins Yonge north of York. By the next surviving edition, dated 1821, the line dips south, reaching York near Queen Street. This reflects the post-1813 realignment of the road into the town.

1821 – Source, University of Toronto

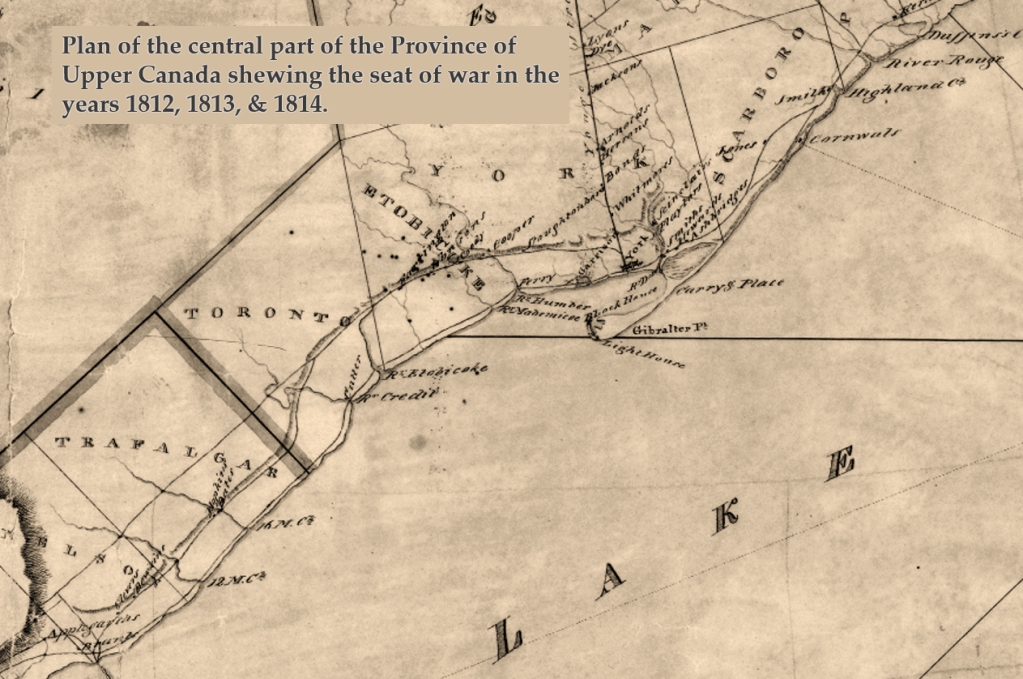

A provincial map also drawn by Chewett in 1819 but depicting the war years 1812–14 shows the road hugging the escarpment west to Etobicoke Creek, meeting Yonge below the heights.

More than a Name

While the maps show the main road west travelling north, the name remained uncertain. Even the government seemed unsure. In the 1812 Act granting funds for public highways, the legislature listed “Dundas Street” as one project and, separately, “the Road commonly called the Commissioners Road, between the Town of York and the River Credit.”5

The distinction matters. It shows that, on the eve of the War of 1812, the road west from York had not yet settled into a single identity.

After the war, however, having the name Dundas brought funding. Statutes directed money to “Dundas Street,” even when the public used other routes. A petition from 1815 captures the irony:

But as your Memorialists are bound by the Act of the Legislature to lay out the money allowed for the repairing the Public Highway throughout this Province, on Dundas Street only…and as the said Road has not been travelled by the Public for several years past…your Memorialists therefore wishing not to expend the Public Money entrusted to them for repairing of Roads, on a Road that will not, in their opinion, be permanent, they therefore humbly pray that Your Excellency will be pleased to order a proportion of the money allowed by the Legislature, to be laid out on the front Road.6

The commissioners knew the public had already shifted south. But bureaucracy, not need, determined which road was improved.

Brockton’s New Dundas

In the area that became Brockton, this mattered. The first trail to bear the Dundas name, likely following the Davenport route, faded from the map.

A newer line, following another Indigenous path on high ground between the swamps near Queen Street and Garrison Creek, led more directly from Cooper’s Mill toward the town and Fort York. That route claimed the name Dundas.

This re-alignment defined Brockton’s geography. The old Dundas, the Indigenous trail favoured by early settlers, was cut short of the Humber. The new Dundas, the military and supply road, took its place.

Our next post will look at how the American occupation of York in 1813 fixed that change and gave us the Dundas Street that shaped Brockton, and Toronto, as we know it.

Maps Referenced

1797 Township of York Map

1834 – Roads in the Township of York

References

- Joy Cohnstaedt and Mireille Macia, “Surveyor’s Notes Solve a Mystery,” Ontario Professional Surveyor 61, no. 4 (Fall 2018): 30–33. ↩︎

- Krista McCracken, “So Long, Dundas: A Colonization-to-Decolonization Road,” Active History (blog), June 17, 2020. ↩︎

- Jeffrey L. McNairn, “Negotiating Sovereignty through Taxation: Direct Taxes, Indigenous Peoples, and Settler Sovereignty in Upper Canada to 1850,” The Canadian Historical Review 106, no. 3 (September 2025). ↩︎

- Emma Stelter, Polishing and Tarnishing the Chain: An Examination of Mississauga Treaties around the Head of Lake Ontario, 1780–1820 (MA thesis, University of Guelph, 2021), 140n. ↩︎

- J. Ross Robertson, Robertson’s Landmarks of Toronto: A Collection of Historical Sketches of the Old Town of York from 1792 until 1837, and of Toronto from 1834 to 1898, vol. 3 (Toronto: J. Ross Robertson, 1898), 281 ↩︎

- Richard Hall to J. Edwards, Dundas Street, 16 January 1810, concerning money spent on roads, Upper Canada Sundries, vol. C-4506, image 463, Library and Archives Canada ↩︎

- An Act for Granting to His Majesty a Certain Sum of Money out of the Funds Applicable to the Uses of This Province, to Defray the Expences of Amending and Repairing the Public Highways and Roads, and Building Bridges in the Several Districts Thereof (6 March 1812), 52 Geo. III, c. 2 (Sess. 1), Statutes of Upper Canada, in British North American Legislative Database, 1758–1867 (University of New Brunswick) ↩︎

- Samuel Wilmot and Richard Lovekin, “Memorial to His Excellency Sir Frederick P. Robinson, K.C.B., Major General Commanding His Majesty’s Forces in Upper Canada, In Council, August 23, 1815,” Upper Canada Sundries, vol. 10394, RG 5, A-I, Library and Archives Canada.

↩︎

Leave a comment