In the post The Sheriff, Secretary, Commander, Widow, and Father-in-Law, I introduced Brockton’s first landowners. Today we’ll look at their own words, written over 200 years ago as they made their case for why they had a fair claim to land in the new province of Upper Canada. A peek into the Canadian archives, at the processes and personalities that turned Indigenous land into colonial property.

I’ve always been drawn to original documents. They’re a direct connection between past and present. You can see the handwriting. You know these pages were touched, seen, and shaped by people long gone, but whose lives briefly intersected with the place we now call home. Like historic buildings, documents are windows into the past.

So what did it take to get a piece of what would become Brockton Village in the 1790s?

The government (or Crown) didn’t give out land to just anyone, although it had no problem taking it. If you wanted a piece, there was a process. That process was laid out in a proclamation issued by John Graves Simcoe in February 1792. The regulation included ten rules.

By his Excellence John Graves Simcoe, Esquire; Lieutenant Governor and Commander in Chief of the said Province and Colonel Commanding His Majesty’s Forces

Grants were limited to 200 acres per person, but officials could approve up to 1,200 acres in some cases. Before 1792, some military officers were promised as much as 3,000 acres or 5,000 acres depending on their rank (David Shank was promised 3,000 acres as we will see below). Before receiving land, petitioners had to swear loyalty to the King and demonstrate they intended to cultivate or “improve” the land. However, many officials were exempt from the improving their lands, a requirement enforced more often for ordinary or common recipients.1

All grants were free of rent, but the Crown reserved all rights to coal, minerals, and naval timber. There was also an administrative fee, but it was charged inconsistently. Not everyone paid.

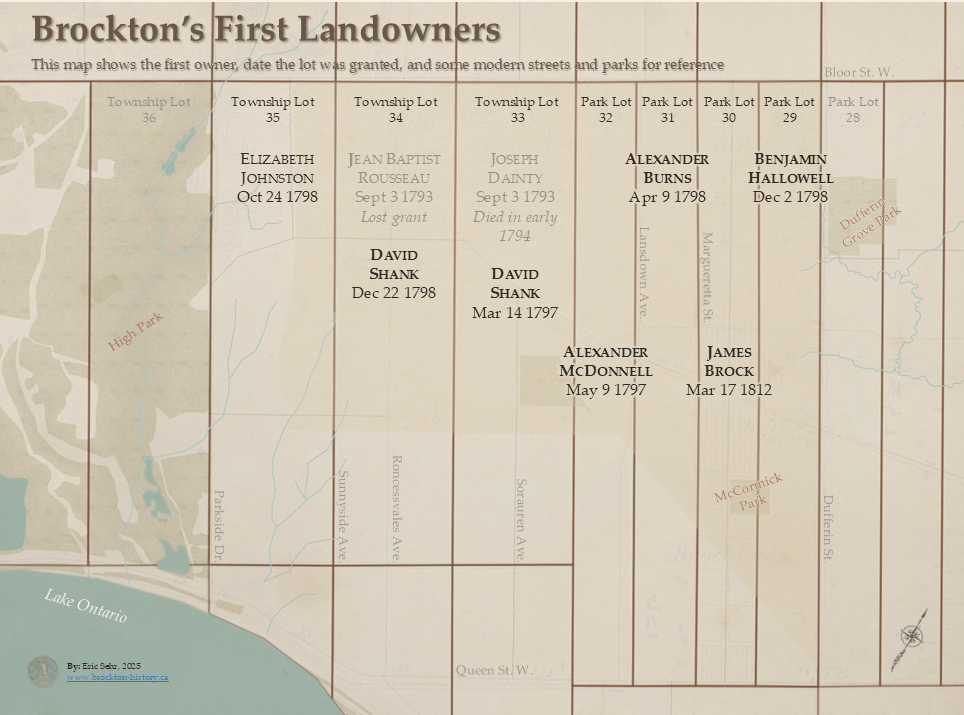

Below is a map of Brockton’s first landowners and excerpts of the petitions submitted by them. A peak into the official archives at the case they made to own a piece of Toronto. The original petitions are available through the Library and Archives Canada. In the interest of space I’ve taken an excerpt of most. If you are interested in looking at the complete copy of one of the petition below click on the link in the captions.2

The Land Petitions

- The Land Petitions

- Elizabeth Johnston – Township Lot 35

- David Shank – Township Lots 33 and 34

- Alexander McDonell – Park Lot 32

- Alexander Burns – Park Lot 31

- James Brock – Park Lot 30

- Benjamin Hallowell – Park Lot 29

- Fragments of Empire

- Sources

Elizabeth Johnston – Township Lot 35

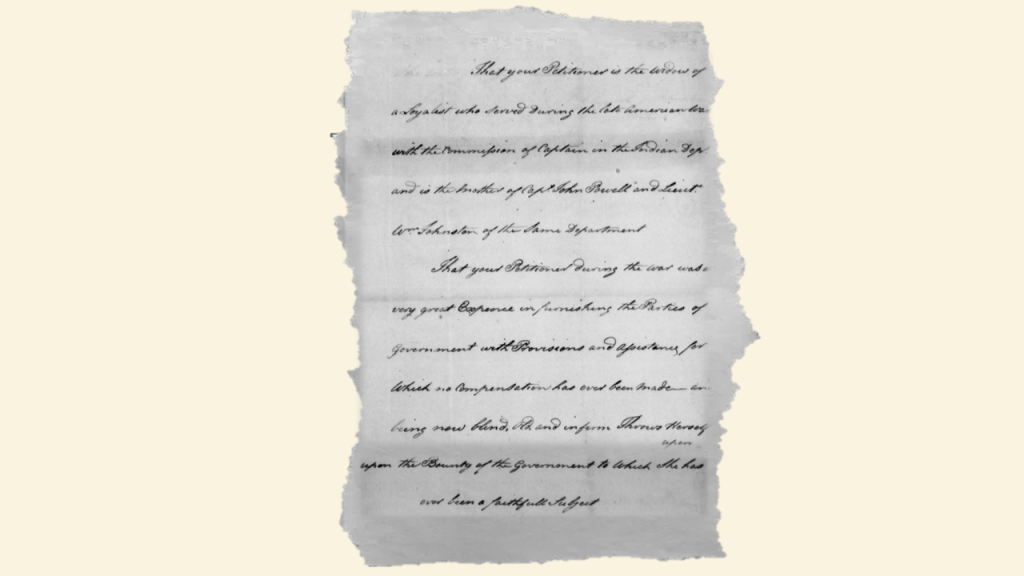

Blind, widowed, and aging, Johnston appeals to the government’s mercy. She emphasizes her late husband’s Loyalist service and her own contributions during the American war, supplying government without compensation. The petition is not written in her own hand. She signed with a mark. The petitioner wrote on her behalf because she was “now blind, old, and infirm.”

Johnston was granted Township Lot 35, which was located between Sunnyside Avenue and Parkside Drive.

Excerpt from Elizabeth Johnston 1797 Land Petition

That your Petitioner is the widow of a Loyalist who served during the late American War with the commission of Captain in the Indian Dep and is the mother of Capt John Powell and Lieut Wm Johnston of the same Department.

That your Petitioner during the war was at very great Expense in furnishing the Parties of government with Provisions and assistance for which no compensation has ever been made—and being now blind, old, and infirm Throws Herself upon the Bounty of Government to which She has ever been a faithfull Subject.

David Shank – Township Lots 33 and 34

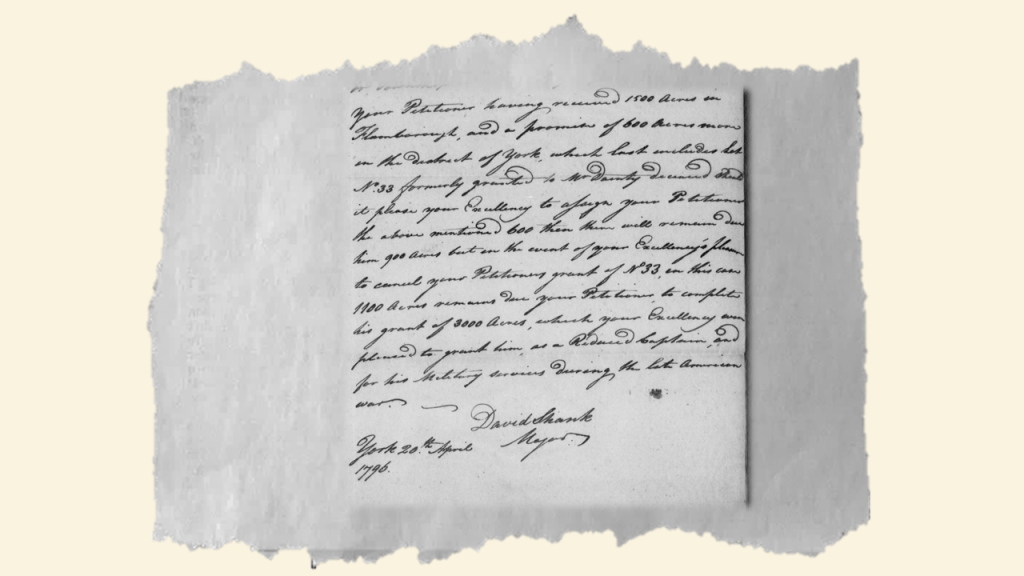

David Shank was a prolific petitioner. Between 1793 and 1798, he submitted at least eight formal land requests. His writing reveals both military confidence and political savvy. He began as part of a group of officers claiming large tracts based on Loyalist service, but soon pivots to more targeted efforts. By 1794 he was petitioning for specific parcels around York (now Toronto), contesting an abandoned claim, and seeking confirmation of a private land purchase.

In 1796, Shank explicitly requested Township Lot 33, which had been granted to a man who died in 1794. He later purchased Lot 34 adjoining his first lot, and sought confirming of the purchase. He also needed to make the case that these lots had not previously been improved.

By 1798, Shank was the largest landowner in what would become Toronto’s west end. He secured 500 acres including Township Lots 33 and 34, stretching from just west of McDonnell Avenue to Sunnyside Avenue.

Excerpt from David Shank 1796 Land Petition for Township Lot 33

Your Petitioner having received 1500 acres in Flamborough, and a promise of 600 acres more in the District of York, which last includes Lot No. 33 formerly granted to Mr Dainty deceased should it please your Excellency to assign your Petitioner the above mentioned 600 acres then [sic] will remain due him 900 acres but in the event of your Excellency’s pleasure to cancel your Petitioner’s grant of Lot No. 33, in this case 1100 acres remains due your Petitioner to complete his grant of 3,000 acres, which Your Excellency was pleased to grant him as a Reduced Captain, and for his military services during the late American War.

David Shank, Major

York, 20ᵗʰ April

1796.

Shank was granted Lot 33 in 1796. Two years later he purchased the neighbouring Lot 34 from fur trader Jean Baptist Rousseaux. Below Shank writes to the Council and President Russell seeking a royal stamp of approval for the purchase.

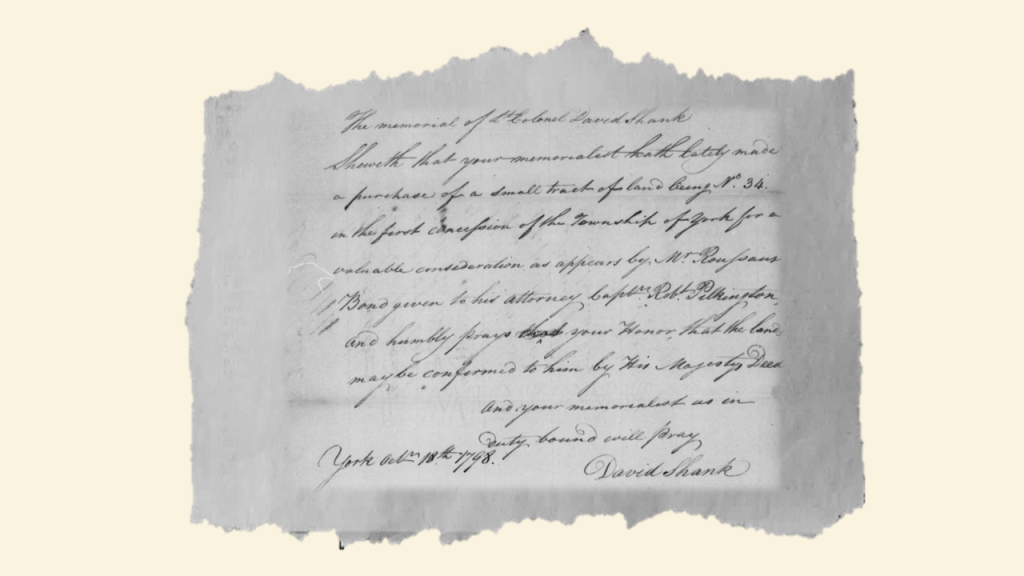

Excerpt from David Shank 1798 Land Petition for Township Lot 34

The Memorial of Lt. Colonel David Shank

Sheweth that your memorialist hath lately made a purchase of a small tract of land being No. 34 in the first concession of the Township of York for a valuable consideration as appears by Mr. Rousseau. Bond given to his attorney, Capt. Robt. Pilkington, and humbly prays your Honor, that the lands may be confirmed to him by His Majesty’s Deed.

And your memorialist as in Duty bound will pray

York Oct. 18th 1798

David Shank

Alexander McDonell – Park Lot 32

Petitioning on behalf of his sons Alexander and Henry, McDonell asked to expand their holdings in Marysburgh (Prince Edward County). It’s the voice of a patriarch securing land for the next generation. Despite being based far from York, Executive Council granted him 100 acres of land west of town. He received Park Lot 32, which stretched between Lansdowne Avenue to a point just west of McDonell Avenue (presumably named for him long after he died).

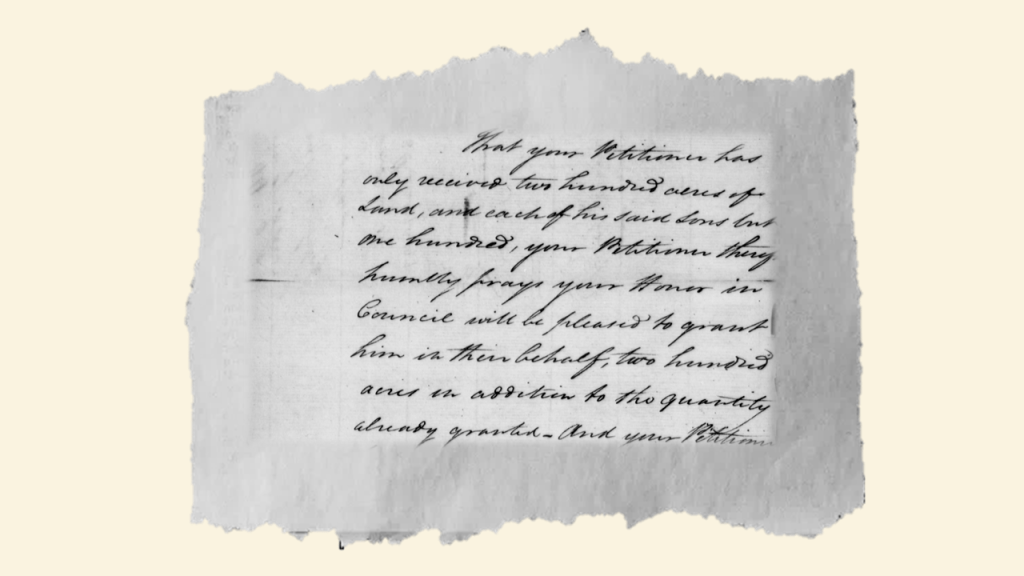

Excerpt from Alexander McDonell 1797 Land Petition

That your Petitioner has only received two hundred acres of Land, and each of his said sons but one hundred, your Petitioner hereby humbly prays your Honor in Council will be pleased to grant to him in their behalf, two hundred acres in addition to the quantity already granted.

Alexander Burns – Park Lot 31

Burns submitted two petitions. His first, in 1796 as a newcomer from Nova Scotia. He stressing his loyalty to the Crown and Constitution and asked for a general land grant.

By 1798, Burns had become secretary to the President Peter Russell and probate registrar, living and working in York. He appealed for land in and around the capital, arguing that others in government had already received similar grants. He was awarded Park Lot 31, stretching between Lansdowne Avenue and Margueretta Street.

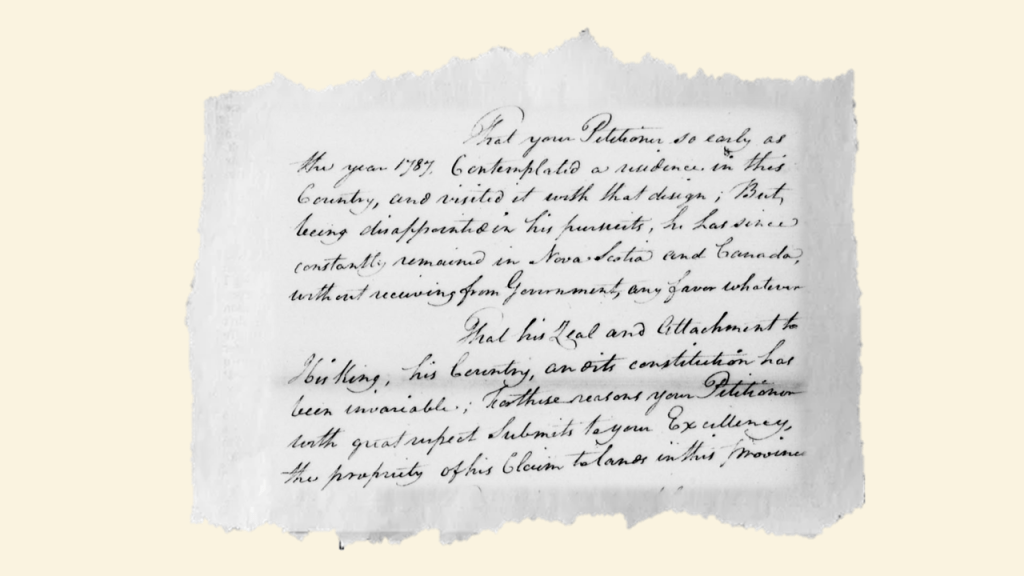

Excerpt from Alexander Burns 1796 Land Petition

That your Petitioner, so early as the year 1797, contemplated a residence in this Country, and visited it with that design; But, being disappointed in his pursuits, he has since constantly remained in Nova Scotia and Canada, without receiving from Government any favour whatever.

That his zeal and attachment to His King, his Country, and its constitution has been invariable; To these reasons your Petitioner with great respect submits to your Excellency the propriety of his Claim to lands in this province.

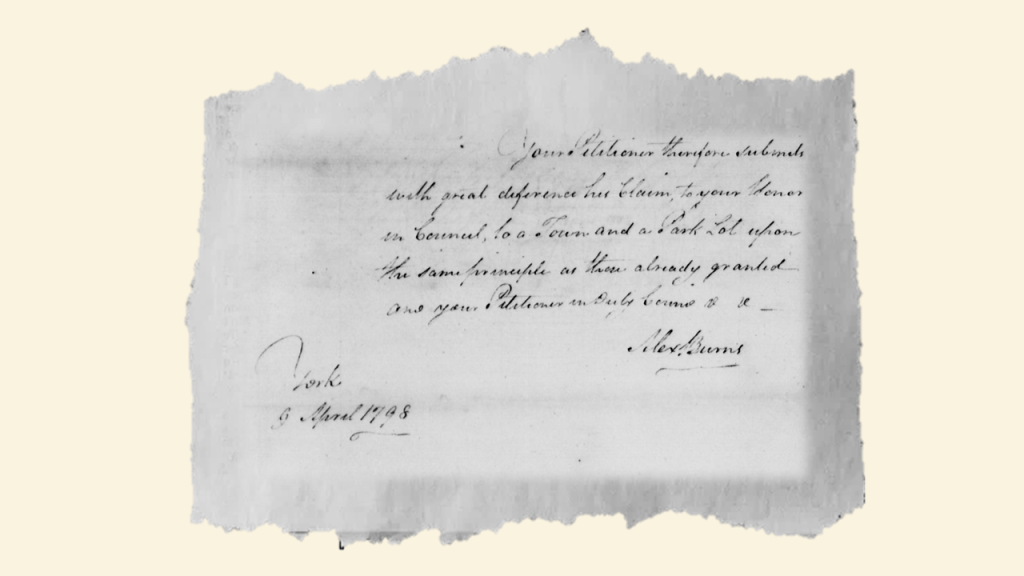

Excerpt from Alexander Burns 1798 Land Petition

Your Petitioner, therefore submits with great deference his claim to your Honor in Council, to a Town and a Park Lot upon the same principle as those already granted and your Petitioner in duty [sic].

Alex Burns,

York

9 April 1798

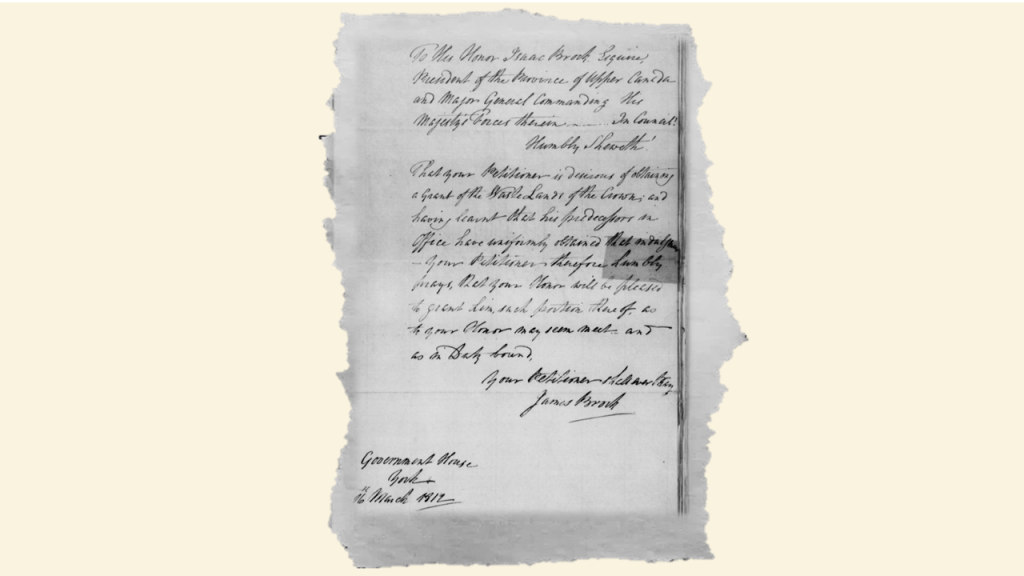

James Brock – Park Lot 30

Brock’s 1812 petition is brief. He simply writes to his first cousin Isaac Brock, the President of the Province (Lieutenant Governor Francis Gore was in England) and states that as an official, he’s owed the same land entitlement afforded his predecessors. His cousin granted him Park Lot 30, which unusually had not granted in the late 1790s. It was the only Park Lot still held by the Crown.

James Brock’s 1812 Land Petition

To His Honor Isaac Brock Esquire,

President of the Province of Upper Canada

and Major General commanding His Majesty’s Forces therein—in Council.

Humbly Sheweth:—

That your Petitioner is desirous of obtaining a grant of the Waste Lands of the Crown; and, having learnt that his predecessors in office have uniformly obtained such indulgence, your Petitioner, therefore, humbly prays that your Honor will be pleased to grant him such portion thereof as to your Honor may seem meet—and as in duty bound,

Your Petitioner will ever pray,

James Brock

Government House, York,

26th March 1812.

Benjamin Hallowell – Park Lot 29

Hallowell submitted four petitions in 1797 and 1798. In his first petition he emphasizes his arrival in the Province from Great Britain with his son-in-law, the Chief Justice. In the one shown below, he asks for a 100-acre lot behind York. In 1798, York’s population was still around 200. Simply moving to the Town while and being a rich Loyalist was noteworthy.

Hallowell was granted Park Lot 29, stretching from Dufferin Street to just west of Sheridan Avenue.

Benjamin Hallowell’s 1798 Land Petition

To His Honor Peter Russell Esq., President, Administering the Government of Upper Canada

The Petition of Benjamin Hallowell Esq.

Humbly Sheweth,

That as your Petitioner is a Resident in the Town of York, Your Honour in Council will be pleased to grant to him, one of the Hundred Acres Lots in the Rear of the said Town, upon such terms and conditions as to your Honour shall seem meet – and your Petitioner as in Duty bound will every pray –

Benjamin Hallowell

Fragments of Empire

These petitions are fragments of empire, written at the edge of a growing colonial state by people seeking position, reward, or survival. Some were insiders claiming what they saw as theirs by right; others appealed through hardship, service, or family ties. Together, they offer a brief glimpse into lives that might otherwise be forgotten. In just a few lines, they reveal something of each petitioner’s social standing, family, and place in the new province.

Sources

- John Clarke, Land, Power, and Economics on the Frontier of Upper Canada (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001), 182. ↩︎

- Library and Archives Canada. “Land Petitions of Upper Canada, 1763–1865.” Government of Canada. Accessed June 12, 2025. https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/land/land-petitions-upper-canada-1763-1865/Pages/land-petitions-upper-canada.aspx. ↩︎

Leave a reply to 📓 BN003 – Deciphering a 19th-Century Will. Pretty tough. – Brockton: A Lost Toronto Village Cancel reply